Log (rss)

24.07.2025 // Thinking of Stonehenge in Manhattan

New York City, United States ⬔

The past four weeks have taken me from Bath to London to New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania—leaving me with just enough time to catch my breath. Amidst the hustle and bustle, I had a few parting thoughts that have stuck with me about a small day trip we did in England, thoughts which are broadly pertinent to travel and living generally.

Shortly before leaving the UK, we went to Stonehenge and it brought me back to a younger self who was just beginning to discover the world. Up to the very day we went, I had doubts about whether to make the trip over. It is a busy time as we approached the end of our visit to Bath. Lots of travel awaited, and as travel accumulates in my past and future, I begin to enjoy static moments more and more.

Nonetheless, the clutter of logistics, work, and everyday tasks can also cloud vision. In the end, how could I not go? The site was less than two hours away and there are no guarantees I will ever have the chance to see it again. The awareness of a present both fleeting and latent with possibility is something that has always characterized my outlook on life. And yet, there are so many forces in our every day that increasingly try to obscure the value of experiencing, living, contemplating. Deciding to go to Stonehenge was a reassertion that each day and each minute is not to be taken for granted.

Beyond the inertia of banality, there is also cynicism: why go? Isn't it just an overhyped commercialized sort of place? These are the whispers and judgements that try to chip away at the value of something because it is too popular, too well-known. I know that my younger self was almost deaf to this type of cynicism. After being denied mobility and possibility for so long, the inherent of value of discovering and exploring and learning and experiencing seemed too obvious. It is this instinct that has driven me to go rogue on trip itineraries, like that time I refused to leave Istanbul without visiting the Hagia Sophia and the Blue Mosque. Today, I am proud that at sixteen I had the foresight to do that; I haven't been back to Istanbul since.

In Walker Percy's "Loss of Creature", the author reflects on how modern institutions, such as school or mass tourism, and the expectations we develop as a result of being embedded in them, alienate us from that which we wish to encounter and access. Percy toys with ideas on how to reclaim experience, eluding cliché, disappointment, and cynicism. Growing up, the inherent value of experiences revealed itself to me as an obvious contrast to the relative scarcity, constraint, and struggle I had had to live through. As my access to the world has swelled, have I lost sight of this?

The special feeling that still springs within, whether at the foot of Stonehenge or on the crisscrossing streets of Manhattan, makes me think not. I still feel like the luckiest person in the world, just like when I saw the rising domes of the mosques in Istanbul or the black sand volcanic beaches of Guadeloupe—-the drive to live is still there, even if I have to make a greater effort to tear down some of the pressures and expectations that adult life has brought with it.

- Andrea

03.07.2025 // Imposing Software

London, England ⬔

I have written before about the importance of software that is portable. One great quality of such software is that it avoids being imposing. The ideal software should allow us to use whatever stack of software we want without forcing a bunch of unwanted dependencies onto us, otherwise it becomes what I want to coin as imposing software.

An example of imposing software would be a bank authenticator that is limited to only a small set of platforms. A more insidious example of such software would be collaborative software or software where, because others use it, you must use it too. This can be Google Docs, which in order to collaborate with others forces you to use a web browser, which in turn forces you to use a specific set of software and hardware, which in turn can make your hardware obsolete. Another example is iMessage, which in a group where not everyone uses iPhone, converts the group chat into a downgraded experience where images are of lower quality. Android users in such a group chat are shamed with green message bubbles.

- Marc

22.06.2025 // On Days Like These

Bath, England ⬔

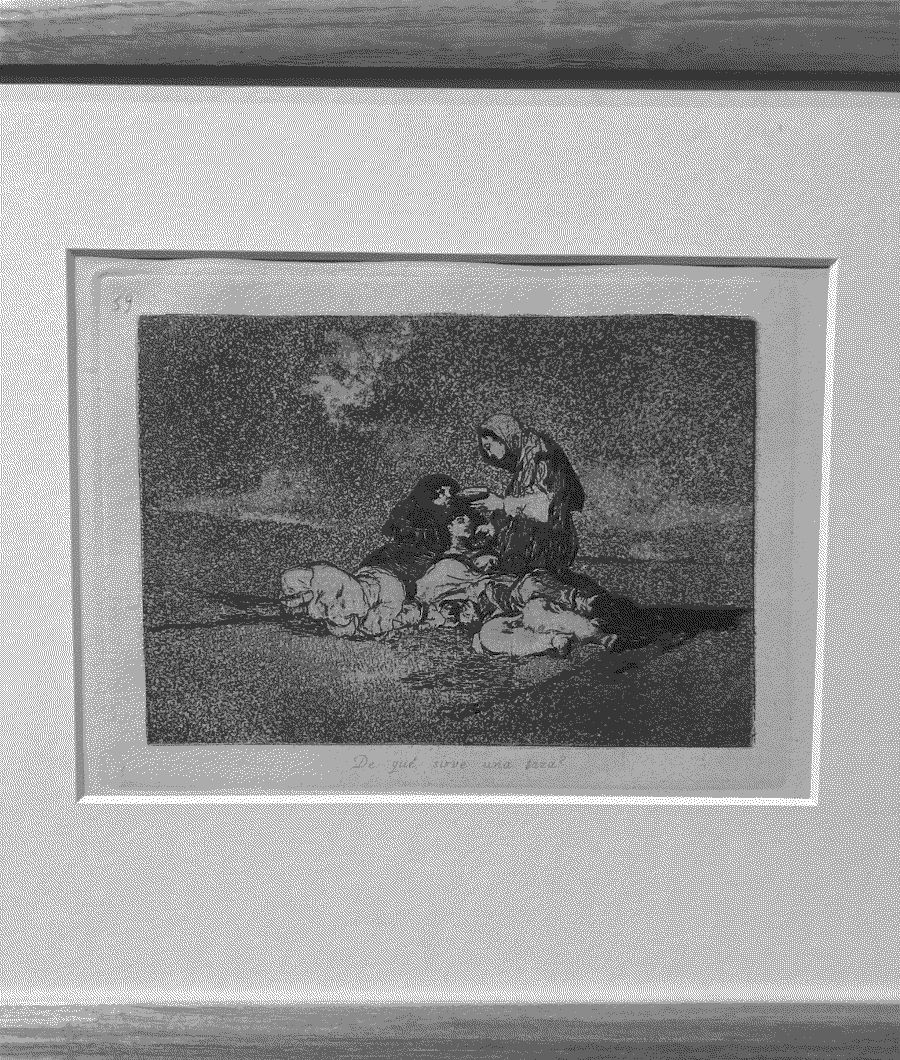

On days like these, when the caprice of a handful of men threatens to extinguish all life and all joy, I can only hope for lucid, human encounters like the one I had today, in a corner of an art gallery, with a print from Francisco Goya's series Los desastres de la guerra [The Disasters of War].

A reminder that we have no need for more Napoleons in this world, a desperate wail etched into metal and paper, an admonition for all the lives needlessly lost to "caprichos enfáticos" ["emphatic caprices"], as Goya called it, and a testament to a shared sense of horror in the face of a relentless unleashing of war and violence that spans centuries. Goya's prints are as necessary and vital now as they were when he first crafted them as a witness.

- Andrea

P.S. The gallery's description of this piece mentions the deadly famine that Goya depicted in this print. However, it fails to mention that the famine was the result of the French army's siege on Madrid.

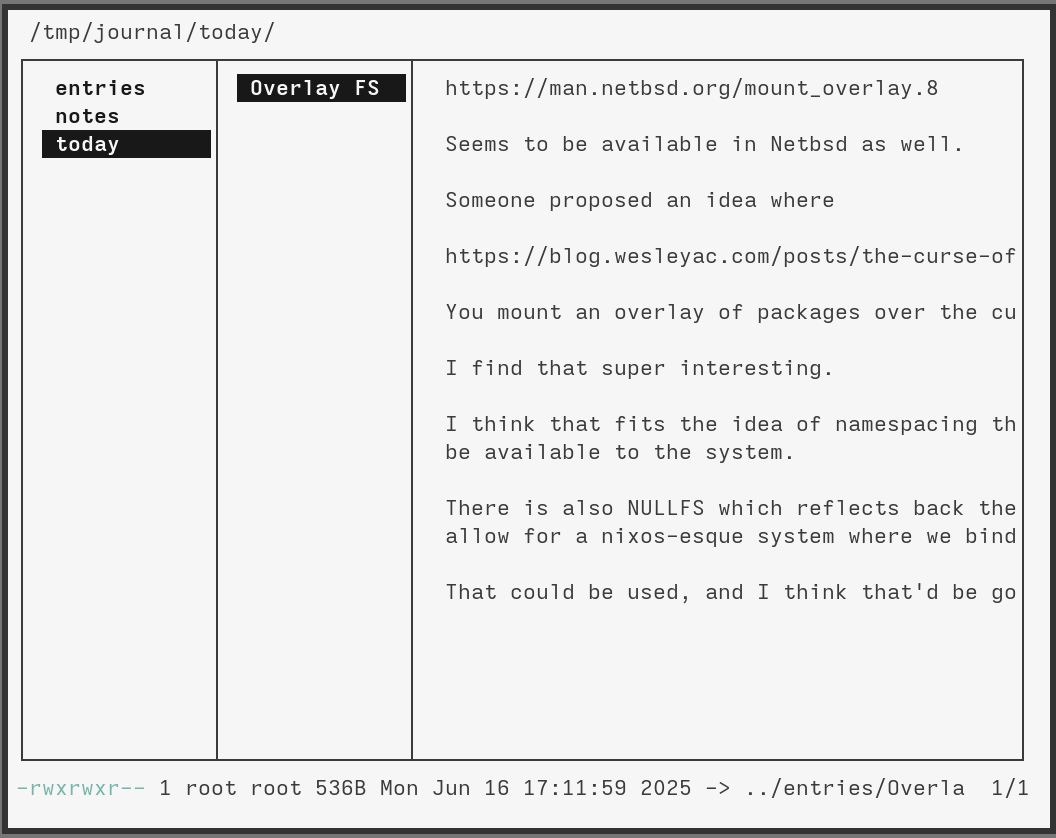

20.06.2025 // Filesystems are Composable Interfaces

Bath, England ⬔

As a programmer, I have had numerous epiphanies that seem so obvious in hindsight. One such realisation came as I was exploring user-space file systems. Any system that exposes simple file formats allows for a large variety of preexisting programs to interface with it. If you expose your data as CSVs then Excel, Google Sheets, Numbers, and Libreoffice are able to open and make all kinds of modifications, calculations, etc.

Arriving at this basic premise doesn't require too much effort, but what is less explored and, perhaps, less obvious is that it is possible expose different "views" of data so that different programs can understand and interact with the data. I've been investigating this with my new program caldavfs (still WIP). I started writing caldavfs because I wanted a way to sync my custom notes between different devices and be able to view and open these notes easily on my phone. Since iCalendar supports VJOURNAL, I thought it'd be cool to expose files that I can write in my regular text editor, and have those be saved afterward as VJOURNAL files that I sync with my caldav server.

Typically an iCalendar file has the following format:

BEGIN:VJOURNAL

UID:19970901T130000Z-123405@host.com

DTSTAMP:19970901T1300Z

DTSTART;VALUE=DATE:19970317

SUMMARY:Staff meeting minutes

DESCRIPTION:1. Staff meeting: Participants include Joe\, Lisa

and Bob. Aurora project plans were reviewed. There is currently

no budget reserves for this project. Lisa will escalate to

management. Next meeting on Tuesday.\n

2. Telephone Conference: ABC Corp. sales representative called

to discuss new printer. Promised to get us a demo by Friday.\n

3. Henry Miller (Handsoff Insurance): Car was totaled by tree.

Is looking into a loaner car. 654-2323 (tel).

END:VJOURNAL

And so what caldavfs essentially does is take those files and build a view of them that is easier to edit and write, allowing you to use your tool of choice when engaging with the files.

What I realize, then, is that files are essentially a protocol, almost like REST, that expose an interface that contains methods, such as: read, write, stat, readdir, etc. Applications that work with files call those methods to perform operations. This is very similar to a message-passing system with late-binding similar to Smalltalk. While drafting out this entry, I did a quick search and found that, naturally, I am not the first one to have made this observation.

The paper also highlights another challenge that I perceived: when you try to fit a file-like interface everywhere, cases arise where the abstraction breaks and become confusing. For example, what does it mean to cp -r a process tree? Does it create a snapshot? What operations are supported?

It's a challenge I faced with caldavfs. It works great as I am able to create notes using any editor I want, and I can use rm, cp etc., to make modifications. At the same time, files do not necessarily map cleanly onto iCalendar format. For example: directories don't exist in ical, summaries are not unique but file names are. Then, there are a lot of cool features that are tougher to represent with files: note linking, categories, event types, etc. How should those be represented? It is not obvious.

This seems to be the Achilles' heel of composable systems, these abstractions become loose and open to interpretation. Files are great, but maybe not the best foundation. Maybe abstractions from Functional programming would be better? Maybe lenses should be the universal interface?

- Marc

16.06.2025 // Half a Year of Books (Part II)

Bath, England ⬔

From within one of Bath's most charming bookshops, I write the second half of my reflection on books read during the first half of 2025, perched on a wooden balcony laden with shelves, tables, books—overlooking even more books, as a well as smatterings of people chatting and enjoying each other's company. A reminder of what the world can be, at its best, even in the moments that feel heavy under the long shadow of violence. I conclude my overview in the company of books currently being read, wanting to be read, and those that inevitably I will never get the chance to read.

Some Surprises

One of the habits I have picked up on my travels is that of allowing chance and generosity to direct my reading list. I have come to learn that, in most places, readers have a tendency to set up little trading nooks of books. From the kaz à livres encountered while hitchhiking along one those steep winding Guadeloupean roads to the small stack of books sitting in the lobby of L'Alliance Française in Ipanema—new books often find me when I least expect it. Books that perhaps I imagined reading someday, others that I might have otherwise never made my way to.

One of this year's most interesting surprises came from the Joigny food market. Tucked into the side of one of the entrances, I noticed a bookshelf, improbable in a visual field peopled with the weekend's fresh produce and other agricultural products: leafy greens, cheeses, winter fruit, fish, honey, saucissons. The bookshelf was nonetheless a popular spot for the townspeople, many of whom paused there on their way in and out with their Saturday shopping. Intrigued, I leafed through all sorts of books, from cookbooks to thrillers, until something caught my eye: an early 20th century edition of Jean de La Fontaine's fables.

I was familiar with La Fontaine; his most well-known takes on classic fables, such as "The Hare and The Tortoise", are staples of French language classes. Which is to say, La Fontaine inhabited a corner of my brain associated clichés and easy moralism. Even so, the beauty of the little old book won over my prejudices, and I am glad it did.

Far from being the morality tales that I imagined them to me, La Fontaine's 17th century retelling of classic fables is riddled with contradiction, humor, rebellion, and more than a touch of existential angst. At times, the "protagonists" of the fable-poems can appear to embody straightforward moral principles, like the "hard-working" ant of the famous "The Grasshopper and The Ant". However, I found the ant to be portrayed as judgemental and almost cruel in its treatment of the grasshopper; an attitude that was explicitly condemned in some of the other fable-poems in the collection. I was left feeling unsure of La Fontaine's stances throughout. In one fable, craftiness is celebrated, in the next it is condemned as dishonest. I like to think that, perhaps, as La Fontaine re-read and re-imaged these classic fables, he was also intrigued by the contradictions that came to light. Perhaps, rather than handing out morals, his work actually highlights the fact that trying to extract straightforward lessons from life is impossible.

The biographical information provided in the book lets me entertain that hypothesis. La Fontaine lived during the reign of Louis XIV, the powerful Sun King, but led a life that feels uncannily modern. Exiled for going against the grain and having what was judged by the monarch to be a "dubious" morality, La Fontaine nonetheless succeeded as a poet and garnered enough support to live from his art. Almost atheistic before his time, but suddenly pious when faced with death, La Fontaine was self-disparaging, funny, lucid, and self-delusional in ways that feel very human. Rather than going around moralizing, I find that La Fontaine crafted beautiful poetry through which he reflected on what it means to live a good life. He also contributed to important discussions about power, art, governance, and education, but I'll stop myself here.

Thus far, there have been two more surprising reads this year. One also came from the Joigny market bookshelf, the play Athalie by Jean Racine. When I picked it up, my only expectation was to read a work by a "classic" French author that I had not read yet. I ended up enjoying a great play that posed some very pertinent questions about power, violence, and freedom (it was "softly" censored during Racine's lifetime, posthumously considered to be one of his greatest works). The second surprise thought-provoking book was a gift of sorts from a good friend, who suggested I read Don't Sleep, There Are Snakes: Life and Language in the Amazonian Jungle by the missionary-turned-linguist Daniel L. Everett.

Our Times

As it might be apparent from the last section, I cannot help but associate what I read with the challenges we face today—even if it's a poetry book about talking frogs and dogs from the 1700s. It is one of many reasons that I am particularly unreceptive to the assertions that studying literature is "useless".

As a result, I could have honestly featured many of the other books that I have read this year in this section: from Umberto Eco's depiction of socioeconomic inequality in The Name of the Rose to the questions raised by Tanizaki Jun'ichiro with In Praise of Shadows that foreshadow current debates on globalization and representation.

I chose to feature two works here that for different reasons touch on topics that are near and dear, Ce que c'est que l'exil by Victor Hugo and 10.000 horas en La Silla Vacía: Periodismo y poder en un nuevo mundo by Juanita León.

After reading Les Misérables during university, I developed a soft spot for Victor Hugo and his sense for over-blown grandiosity and drama. Hugo's style feels acutely that of another era, but many of his biggest concerns are timeless. The basic premise of Les Misérables, that of the injustice of condemning a man to forced labor for the hunger and misery he was born into, continues to resonate in global demands for greater equity and justice.

With Ce que c'est que l'exil, which roughly translates to The nature of exile, Hugo reveals the price that he had to pay for his activism as well as his opposition to the reign of Napoleon III. While I had been vaguely aware that Hugo had been, at some point, exiled to the islands in the English Channel, I initially processed this fact as historical trivia, without much thought. However, through this book, Hugo acutely transmits what it is like to be condemned to exile, persecution, spying, and harassment for 20 years. Beyond appreciating Hugo the literary legend, I felt that I approached Victor the man.

At the same time that I recognized and lamented the struggles Hugo described, reading Ce que c'est que l'exil ultimately gave me hope that the ideals for justice and peace that can feel hopelessly out of reach today could one day materialize. Among the "radical" ideas that Hugo was persecuted for in his time: his support for universal suffrage and public access to education, his opposition to slavery, domestic abuse, and tyranny. More than describing his own suffering, Hugo highlighted the importance of persistence in the fight for greater justice, and the key role of solidarity, even in moments that can feel so isolating.

There is a lot of talk of our contemporary collective disenchantment, of a vacuum left in the wake postmodernism that needs to be filled. It is a discussion that awakens all my skepticism, as it often leads to claims that as humans we essentially "need" religion. I won't go down this rabbit hole now, but I will recognize the need for a coming together that is constructive and empathetic. In my eyes, Hugo's romanesque writing (even with its flaws) shows a way. I was sad to find that there was no English translation for this text which, like with Carranza's poetry, made me once again entertain ideas of translation and dissemination.

Similarly, my other pick for this section is not available in English, as far as I know. 10.000 horas en La Silla Vacía: Periodismo y poder en un nuevo mundo is a reflection on contemporary journalism in Colombia written by Juanita León, the founder of one of the leading independent news outlets in the country, La Silla Vacía. In her book, León looks back on how it all started and how, despite all the challenges, La Silla has persisted as an independent outlet. This necessarily involves an overview of Colombia's recent economic and political history. Not only did I fill in some gaps in the understanding of our recent history, but León focuses a lot on identifying and describing the mechanics of power. Colombian society is incredibly conservative and hierarchical; Colombians have some of the worst prospects for social mobility in the Americas. From the outside, we all vaguely perceive the structures that keep power in place and concentrate it, but León allows the reader to peer within these machinations.

At the same time, León candidly reveals that to keep La Silla Vacía afloat she has to make use of all those social markers and contacts that are the key to getting anything done in Colombia. León must operate within the very system her outlet critiques, which generates tensions and difficult ethical dilemmas. I find her transparency around the logistic issues of keeping a media outlet running so important when thinking about how to create alternatives, as she did when she decided to launch an alternative to the big legacy media.

At a moment that violence is rising again in Colombia, in which it feels like the country is stuck in a hamster wheel of death, León's book provides precious understanding. This light that journalism, testimony, and research, all offer is vital to warding off the informational darkness that violence requires to thrive. One of the Colombian journalists that I admire the most, Javier Darío Restrepo, spoke widely about this during his lifetime. I reflected a bit on his writing last year while in Cyprus.

Other Interesting 2025 Reads

To conclude, some final books that prompted me to reflect on literary form and genre. From Sontag's essay in the form of a list to Shambroom's ekphrastic history-essay, these works serve as a reminder to imagine more.

- Duchamp's Last Day by Donald Shambroom

- L'exil et le royaume by Albert Camus

- L'homme qui plantait des arbres by Jean Giono

- Notes on 'Camp' by Susan Sontag

- Andrea

07.06.2025 // Half a Year of Books (Part I)

Bath, England ⬔

When I first posted the "August Reads" entry in 2024, I imagined ambitiously that every month I would upload a "review" of the books I read. Almost a year later, I would like to rescue that idea. There are so many interesting books that I have read and re-read since then, but I will restrict myself to some scattered reflections on the past half year of reading.

New Favorites

So far, this year's grand revelation is The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco (along with Camus' Le mythe de Sisyphe, but I am still working on it). In one novel, Eco managed to speak to my childhood love for detective novels, my teenage nerdiness for learning as much as possible about anything and everything (including medieval Europe), and my present concerns about the nature of truth and living with truth in an ever-changing world of difficulties and possibilities. The prose was poetic and funny, page turning and almost inscrutable. Timeless and present with a 12th century setting, it is a transcendental book that I hope will always keep me company.

Before The Name of the Rose, I started the year off with Italo Calvino's Invisible Cities, and it provoked a very different type of awe. While Eco (and Camus) read grandiose and monumental, in many ways, Invisible Cities is quiet, but powerfully so. It achieves timelessness in a very different way, too. Like Eco, Calvino places us in a historical past, that of the Silk Road, Marco Polo, and Kublai Khan. However, where Eco as a medievalist is relatively rigorous, Calvino writes loosely and a parallel dream world arises from the history he is inspired by. Fantastic city after fantastic city, I felt more and more drawn into the world Calvino pieced together, a world that uncannily drifted very close to home, every so often, especially in the moments that, at first glance, appeared to be the most dream-like.

I extend an "honorable mention" to In Praise of Shadows by Tanizaki Jun'ichirou, which I read in the French translation (Éloge de l'ombre). The beautiful long-winding sentences unfurled quietly into piercing insights, not only about the development of Japanese culture up to the 20th century, but also with regard to what it means to attribute and develop value judgements within a cultural context. What is beauty? What is goodness? Tanizaki presents a calculatingly messy train of thought that waxes poetic. It is essay-poetry, in a sense. At the same time, I could not fully embrace Éloge de l'ombre due to the lingering taste of an essentialism that felt almost deterministic. At a moment of rising insularity and nationalisms, I find the quest for "essences" troubling. There is a fine line that shapes the difference between understanding how aesthetics and ways of doing arise from culture, and prescribing a certain way of doing as essentially "Japanese". And while Tanizaki displays a degree of self-consciousness as to the development of cultural norms within specific contexts and circumstances, he also does not hesitate to issue very clear-cut assertions that read too much like givens or truths about what a group people is "essentially" like. Nonetheless, a book I look forward to revisiting.

Illuminations

I have read two illustrated works during these first six months of 2025, Jungle Nama: A Story of the Sunderban by Amitav Ghosh and Salman Toor, and Looking for Luddites by John Hewitt. Both books made me reflect on the interplay between text and visual arts, which I think is very pertinent at a time that many predict (and/or lament) that both will be mechanized away.

This was my second reading of Jungle Nama, which I bought from Araku, a coffee shop we frequented during our stay in Bengalore. Looking for Luddites was found at a magazine and stationary shop I am fond of in Bristol: Rova. In a way, I encountered both books as artefacts that caught my passing eye.

For many decades, the predominant mode of thought has placed illustration as subservient to the written word. And in a way, illustration could even be considered as a "threat" to the seriousness of a book. Are picture books perhaps not "real books"? Jungle Nama and Looking for Luddites demonstrate that it is not so (as do so many other brilliantly illustrated books, such as the Alice books). Illustrations here prove to be not merely decorative, but rather are as essential to the storytelling as the text. The unique perspective or "eye" of the illustrator (even in the case of Hewitt, who is also the writer) cannot be subtracted away.

It is interesting to think about these books together, what does the retelling of a Bengali myth about the Sunderban mangrove forest have to do with the retelling of the Luddites' uprising against industrialization in Northern England? So much, it turns out, as both little books explore the nature of human greed as well as the complex relationships between human settlement and the natural world. In both works, authors and illustrators look to the past to raise timeless concerns that are among the most urgent today due the generalized use of AI and the destruction of our ecosystems. In both works, the "expendability" of human life mirrors the "expendability" of ecosystems, animals, and all other forms of life.

A parting thought related to pertinence, I read Jungle Nama at the same moment that both India and Pakistan were, once again, at the brink of war. Authored by an Indian writer and illuminated by a Pakistani illustrator, the book stands as a powerful contrast to war, illustrating what could be possible by coming together instead.

Reconsiderations

I have recently re-read two books of Latin American poetry, the Chilean poet Alejandro Zambra's Mudanza and María Mercedes Carranza's El oficio de vivir, the latter of which I wrote about for the original August Reads entry. I bought both books at the Bogotá Book Fair (FILBO) in 2024, and I picked them up again when I was feeling nostalgic about not being at FILBO this year.

First, I realized that I enjoyed both books more on the second read, which confirms by experience the well-known adage that good poetry must be re-read. In a sense, this reencounter with Zambra and Carranza is part of a multi-year reconciliation with poetry that first begun with Louise Glück. I had initially failed to connect with poetry, despite my love for reading, and I then struggled with it as a university student after the "Poetry 101" teaching assistant took great pleasure in announcing that the course was meant to "weed out" students from the English major. I survived the course, but ultimately chose not to major in English.

I had already appreciated Carranza's work on my first read, however, I couldn't quite count it among my favorites because I found the collection's bleakness to weigh too heavy. Carranza masterfully conveyed the hollow feelings of depression, and it was almost too much to bear. On a second read, however, my initial reticence has given way. The shock of encountering Carranza's profound listlessness and melancholy has subsided, and I felt like this time I could better perceive the beauty she crafted from the shadows. Despite of everything, glimmers of life shone through the despair and with the despair. It is a special book, compiled by Carranza's daughter with a lot of thought and care. I wish Carranza's poetry could be better known outside of Colombia. (And I wish I could translate it.)

My thoughts have strayed far, as usual, so I will continue my 2025 book reflection in a second entry.

Other Interesting 2025 Reads

- "The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House"

- "Permacomputing Aesthetics: Potential and Limits of Constraints in Computational Art, Design and Culture"

- Andrea

01.06.2025 // Café colombiano

Bath, England ⬔

For most of my (relatively brief) adult life, I took a bit of pride in being the Colombian who did not drink coffee. The association between coffee and Colombia is almost as tight as that of spicy peppers and India or potato and Eastern Europe. And yet none of these quintessential crops are "native". The potato and the peppers are technically "ours", they are native to the Americas. Meanwhile, coffee is traced to the Arabic Peninsula and the Horn of Africa. I cannot deny, however, that the "tinto" (a watery black coffee) is as near and dear to Colombians as tomatoes are to Italians. Nor can I deny that my childhood memories of lazy Saturday mornings are steeped in the aroma and flavor of a very milky café con leche. Almost everyone in my immediate family grew up drinking coffee (even if in very low doses).

Still, beyond the nostalgia for the childhood café con leche accompanied by a cheesy arepa and huevos pericos, I did not understand the general public's devotion to coffee. That it was necessary to drink coffee to get through a day was really off-putting to me; I did not want to depend on a drink to live my life. And then, when I first encountered all the different contraptions for "fancy" coffee brewing as a student in Chile, I was dismissive out of ignorance.

Coffee continued to be like a distant cousin seen only at family gatherings until the day I moved to Sweden. From the Arabian peninsula to South America to Scandinavia—the coffee plant has journeyed far. However, sitting in a cozy café in Stockholm with a warm kanelbulle on a dark cold evening, the prospect of a brygkaffe didn't seem all that bad. I could then understand why the Finnish and the Swedish were the top coffee consumers in the world.

Having coffee in Sweden is how I discovered the very first reason why I did not "get" coffee. The coffee we drink in Colombia, and much of Latin America, is incredibly watered down. Not only is our coffee flavorless because of this, but it is also intolerable to drink any stronger because of how burnt the widely commercialized coffee grounds are. In Colombia, we have long been left with bottom barrel coffee, and families have done the best to make it last on a tight budget.

But, it has not always been that way. Arguably, the status quo of Colombian coffee is a relatively new state of affairs.

After discovering that drinking coffee could truly be pleasurable in Stockholm, I was much more open to reencountering coffee in my own hometown. In Bogotá, Marc and I hopped from café to bookstore to café to art gallery, and gradually we discovered what a pour-over was, what a V-60 was, what a Gesha was. At one of the coffee shops in the historic Candelaria neighborhood, the owner shared his own coffee journey with us as he brewed our cups. After growing up in one of the most troubled neighborhoods of Bogotá, he only got his very first taste of excellent Colombian coffee while abroad in South Korea. Shocked, he became convinced that all Colombians should be able to taste and enjoy what was being massively exported away as a luxury. After training as a barista, he brought café de especialidad to his neighborhood, first, before opening up a second shop in Candelaria.

So, what was Colombian coffee like before all the good beans were exported away? The answer lay much closer to me than I imagined. Wanting to share the delicious coffee with my family of avid coffee-drinkers, I invited them to a drip coffee demonstration at Xue Café. I was excited to see their reaction, but instead of the shock of novelty, it was the warm surprise of an unexpected reencounter that animated their conversation. They insisted: this was the way my great-grandfather brewed coffee. No, not with a ceramic V-60 nor with specialized water pourers and electronic scales. He fashioned his own type of "pour-overs", using cloth filters, a kettle over a fire, and the beans he had grown, picked, dried, and roasted himself. My family had not tasted a coffee like the one they were having in this specialty coffee shop since those days back on the farm.

It had only taken two or three generations for most Colombians to lose access to good quality coffee. Only now the tide is beginning to slowly turn, but good coffee remains unaffordable to many and often perceived as "fancy" and, ironically, as "foreign" and "strange".

Last year, Marc and I attempted to brew our own pour-over or drip coffee for the first time. When we left Colombia for Cyprus, we brought some coffee grounds with us, as a way of bringing along a little piece of home and its aromas. We began our experimentation with some grounds from a local Limassol roaster, wanting to save the coffee from Colombia for when we got the processes just right. We did not know then that coffee brewing would become a multi-month journey. Nor did we expect that we would end up hand-grinding our own beans.

There are plenty of issues with how the world drinks coffee, the environmental and socioeconomic impact of it all, especially when it is Nestle or another unscrupulous company that commercializes the coffee (and many "fancy" specialty shops and roasters are not at all exempt from this). But, I have also seen many small shops, roasters, and artisans fighting to make coffee fairer for everyone. It is not just about putting a nice story or name to a coffee bag. They display prominently how much coffee farmers are paid and lay bare what their profit margins are. Under these conditions that foster transparency and solidarity, when I walk into a coffee shop and see the names of the farms, the places, and the people who work hard to make coffee possible, it makes me feel a little closer to home.

- Andrea

23.05.2025 // The Comma Directory Restructuring

Bath, England ⬔

I've meant to write (and I always mean to write) about our arrival to Bath—which has been truly revitalizing and has offered some harmonious continuity to our time in Devon and Selgars Mill.

However, I have been occupied in the pruning and clipping of previous Comma Directory entries that, over time, seem to have grown unwieldy, outgrowing the categories and sub-categories we have plotted them into. It has taken me some time, and it has got me thinking.

Curatorship is a topic that has long interested me, and it has become more and more pertinent in navigating the complexities we encounter—growing complexities—many would say, as the world grows more and more complex with AI, a changing climate, the threat of war. But I would say, instead, that complexity was already here all along. It could been found in the simplicity of a leaf that photosynthesizes or the star that twinkles in the night sky.

Hence, there is a "primal" need to curate, or categorize, or simplify. These actions are not strictly synonymous, but tightly bound to each other. I think, at least.

The issue with trying to place an infinitely complex experience of existence into neat categories has long been discussed within science, philosophy, technology, art. Our representations of the world are limited, and that is precisely why they are meaningful. By placing limits, which is to say prioritizing some facets of existence over others, we voice a point of view. This is why diversity of representations is so important—but it doesn't mean that limits themselves are "bad." Without limits, without the brain's ability to curate the complexity of each passing moment, decision-making, survival, meaningful and directed action would all perhaps be impossible. It is known, after all, that the "infinite" choice of streaming platforms, food delivery, and dating apps can often be debilitating and paralyzing. As can be the "infinite" flow of news and social media posts.

And these choice-laden systems do not even begin to approach the true complexity of how our planetary systems operate, not to say the universe.

All of this to say, I have been toying around with The Comma Directory's Concepts, Media, and Travel pages. I have been questioning whether having a "Design" category is too broad, and what the difference between design and other creative practices is. And, should sub-categories be included into multiple categories or restricted to a single one? It might not help that lately Marc has been reading the book, What Design Can’t Do: Essays on Design and Disillusion.

Ultimately, what are these categories for? Which in the end is the same as asking: what is The Comma Directory for? Developing a system for categorizing main ideas and themes is at the heart of our founding concept. It is a work in progress, and in a sense, it always will be. The categories will always overlap in some ways that are perhaps uncomfortable, and maybe there will also be some gaps that are hard to fill. Imprecisions.

I can imagine that many may consider that AI is particularly well-suited for this task, with its powered up pattern-recognition. Feed it the texts and have it spit out a systematization that, with the right prompting, could be "better" than anything that we can produce manually. Less time consuming, too. Why not? Maybe, while it is at it, it can also generate the entries and the images.

If making "sense" of the everyday complexities that bombard us is one of the most important functions of our brains, if our ability to make purposeful decisions has to do with our brain's ability to curate, to pick and choose, to categorize and, therefore, judge—then the work we do manually at The Comma Directory is profoundly rooted in what it means to think. In our vibes-bent era peopled with all sorts of energies and traumas, "feeling" feels much more fashionable than "thinking." And while I find modern, postmodern, and contemporary critiques of rationality to be very important, I echo Camus in saying that, while I acknowledge the many limitations of "reasoning", I do not deny "reasoning" in it of itself. And I do not want to automate away the very mental processes that constitute reasoning, and which I perceive to be very closely linked to my own agency and liberty. Not to say that intuition and feeling do not play an essential role, a role that is perhaps more closely tied to reasoning than traditional dualist conceptions of thought allow.

Ultimately, when I sit down to edit, reorganize, redefine, and recategorize, it is almost like I can feel changes starting to blossom from within, in real time, as I focus and tinker with our little website. I feel new questions begin to emerge, ideas begin to form, old ideas begin to transform. Maybe that is also why this entry is growing so much more longer than I anticipated.

There is a pleasure too that comes with all this thinking, of feeling yourself being transformed by interacting with a challenge and all the difficult questions it brings with, even when you do not fully succeed (which is often the case). The pleasure I derive from the curation and restructuring of The Comma Directory is also akin to the pleasure of moving to a new home, finding the nooks and crannies in which different little aspects of life can fit into. Here, the washing, there, the books. It is as much the art of adjusting the space to our lives as our lives to the space. Which is why it has been very fitting to work on The Comma Directory's categorization system at the same time as we have been settling into Bath and creating our short-term home here.

So, what's changed on here? New sub-categories have appeared, emerging from nearly a year's worth of writing and living, which is exactly what we hoped for from the start. I have also re-arranged some major categories within Concepts. For example, "Writing" has become "Creation", to cover a broader range of creative acts that we engage with. Thanks to Marc, each entry has its own page now, and can be accessed via the little square next to the location. Within media, there is some restructuring ongoing related to each "media" type. While we started with just "Books" and "Film", now we have "Articles & Essays", "Lectures", and "Websites". I am working on new ways of displaying a growing list of favorites, and hopefully implement a Reading Journal and a Film Journal. The new "Reviews" sections will include scattered thoughts on the different media types, rather than reviews in the strict sense of the word. I feel joyful about what The Comma Directory has grown into so far, and what it can grow to be with some continued care and attention.

- Andrea

29.04.2025 // Lucidity and the Sun

Bath, England ⬔

Lucidity. A concept Camus explored in a few of his essays, and that in many ways echoes a kind of personal philosophy that Andrea and I have been developing. To us, lucidity means to see the world for what it is, instead of ascribing grand narratives or superstition to it as a way to console ourselves for the perceived "meaninglessness" of existence.

In The Stranger, Camus writes about a man named Meursault and describes his complete indifference to the world. Meursault is meant to be unrelatable. Someone who seems almost inhumane, and so, who would not be able to relate or empathize with us either. Through his actions and attitudes, Meursault reveals what Camus calls "the absurd," which has to do with the perceived absence of meaning in life. However, Camus also introduces symbolism to reveal that as humans, we can rebel against the absurd.

In the very first scene of the book, when Meursault finds out his mom died, his apathetic response is difficult to stomach, as it is later on, when he encounters the titular stranger. In both scenes, Meursault focuses on a light that flickers or the sun that blinds him. His fixation on light during moments in which more "important" things occur, like the death of his mother, increases the distance between Meursault and the reader.

The light and the sun to me represents two things in this book. On some level, the distance we feel between ourselves and Meursault serves as a reminder of our innate urge to care, even when the world appears to be meaningless. An urge to care that Meursault does not seem to experience.

But the depiction of light also serves as another reminder, that when we feel the weight of the absurd the most, the shining light can set a path forward. The light shines on our skin and makes us see, and so it reminds us to be present. When we are present and experience the world for what it is, lucidly, we can revolt against the absurd.

This idea of lucidity and Camus' articulation of this concept was eloquently spelled out in a recent episode of Philosophize This on The Stranger, and I felt myself just nodding along in agreement.

- Marc

27.04.2025 // Ubuntu

Uffculme, United Kingdom ⬔

As AI slop begins to become omnipresent, curation and support will be more important than ever. I think we can carry this anxiety that our artistic efforts will cease to exist if we are replaced by machines.

Here is the thing though: if we collectively decide not to let that happen, it won't. If we continue to buy art and support endeavors we believe in, those endeavors can continue to be.

That's why I think that, today, it is more important than ever to support compelling independent projects and to promote them. That way, we can build the society that we want: one in which artists can thrive without having to resort to tools that go against their ethics.

Recently, I've made an effort to end many of my subscriptions, for example Spotify, and then spend that money instead on artistic, tech, or social projects that speak to me. That does limit my access to popular media, but at least I am more mindful about what I consume.

Recently, Andrea and I booked tickets to go to South Africa. In various Bantu languages, there exists the term ubuntu, which roughly translates to I am because we are. I am excited to learn more about this idea when we are there. For now, the definition I found online really speaks to me, ubuntu "encompasses the interdependence of humans on one another and the acknowledgment of one's responsibility to their fellow humans and the world around them" (Wikipedia). I think the philosophy that underpins ubuntu may be very relevant to face the questions and challenges of our times.

-Marc