Log (rss)

29.10.2024 // Personal Tools

Paramytha, Cyprus ⬔

Recently, I finished up Donald Norman's An Invisible Computer. It's a fantastic book, probably one of my favorite books, and it starts off with a powerful quote:

"The personal computer is perhaps the most frustrating technology ever. The computer should be thought of as infrastructure. It should be quiet, invisible, unobtrusive, but it is too visible, too demanding. It controls our destiny. Its complexities and frustrations are largely due to the attempt to cram far too many functions into a single box that sits on the desktop. The business model of the computer industry is structured in such a way that it must produce new products every six to twelve months, products that are faster, more powerful, and with more features than the current ones."

As much as I like the book, however, there is one important concept that I disagree with. Norman titles and concludes the book with this idea: that technology should be completely invisible. By invisible, he means that technology should blend so seamlessly into our everyday life that we do not notice it is there.

"[.. talking about the goal of technology] The end result, hiding the computer, hiding the technology, so that it disappears from sight, disappears from consciousness, letting us concentrate upon our activities, upon learning, doing our jobs, and enjoying ourselves."

Sounds great in theory, in practice of course what we find is that companies make something that is easy to use, and then do not necessarily act in the users' best interest, but the user is stuck with what the company provided and is neither empowered to seek out other options nor fix it. I think this is an anti-pattern, and I talk about this in depth in my essay, The Curse of Convenience.

However, there is also another section that I found particularly interesting and shines a light on the direction where I think technology should go, which is Norman's idea about what makes a good tool. Norman has this to say:

"Good tools are always pleasurable ones, ones that the owners take pride in owning, in caring for, and in using. In the good old days of mechanical devices, a craftperson's tools had these properties. They were crafted with care, owned and used with pride. Often, the tools were passed down from generation to generation. Each new tool benefited from a tradition of experience with the previous ones so, through the years, there was steady improvement."

I do not feel like modern phones and computers are like this kind of tool. A good retro camera is something we learn inside out, with its quirks and unique abilities, and becomes part of our craft and personality. This is not so much the case with a modern iPhone. Modern technology removes as much personalization as possible and makes it hard to repair for the sake of convenience, looks and ease-of-use. That means that you do not put effort into truly knowing your tool nor personalizing it, and so as a result, do not appreciate it as much. Instead of customizing and learning about your unique device, you buy a new one, that acts just like the old one. Devices become impersonal and invisible.

In a recent interview, Norman laments the fact that his all time best-seller, Design of Everyday Things, did not cover that tools should be designed to be repairable too. To me, repairability is in opposition to his idea of technology becoming invisible. At the same time, I think repairability and customization go hand in hand with his idea that you should feel pride in owning a tool, and that that is what makes a good tool. A device that you tweak and make truly your own, you will care for more and want to repair as well. As I replace parts of my Thinkpad and change the way it looks and feels, I find it becomes more personal to me.

- Marc

30.09.2024 // War and Words

Lofou, Cyprus ⬔

Today we are in Lofou, a small village located 20 minutes north of Paramytha. It is another dreamy place that has preserved its beautiful stone architecture. In the café-restaurant that we sit at, a calm and cool atmosphere gives peace. We are surrounded by books, ceramics, dried plants, wood, art, the blue sky, and a green garden.

I have Javier Darío Restrepo’s Pensamientos: Discursos de ética y periodismo with me, which I read from a beautifully and simply designed armchair. Pensamientos reminds me of home. Life feels joyful.

And yet, whenever I pull up a map, I am reminded that we are now just off the coast of Lebanon. Perhaps an hour-long flight from Gaza. If I zoom out, I notice that we are on the same longitude as Ukraine, we share the same time zone.

I was born surrounded by violence. In Bogotá, you are always on your guard, even if the city is safer now than what it used to be, and a whole lot safer than what other parts of Colombia are still like today. Being here now, in this idyllic village, the contrast feels stark.

During a brief period in my early adulthood, (outright) war between nations went from feeling unthinkable to almost inevitable. I know this isn’t true, violence and injustice have been and continue to be ever-present. The turn of the century was incredibly bloody for Colombia with the "war on drugs." But it does feel that now there has been a broader mental shift: that before war and violence were somehow more unacceptable globally, and so different actors undertook violence in slyer and stealthier ways. Political discourse around military attacks and violent action was not so forthright. Some people may say, as has been said about Trump, “at least they’re being honest now, showing their true colors.”

However, I disagree. I think that the fact that a full-scale war was “unthinkable” for many people was a good thing. The fact that we have mental red lines is important, even if humanity does not always live up to these standards. To me, the goal should be to denounce and expose the ways governments, businesses, and individuals get around what is deemed just or right, and the ways in which hypocracy takes shape. We should hold leaders accountable for lofty speech promoting peace and tolerance, make them meet the standard, instead of giving in and making war and violence an “acceptable” and “inevitable” part of our everyday in the name of "honesty."

For a long time, I’ve felt a natural pull towards pacifism. However, I understood well the people who critiqued it, we need to defend ourselves from those who commit harm after all, don’t we? We need to be able to fight back, right? What’s the alternative?

While I don’t have any answers, I have realized I need to listen to that instinct that protests against violence, conflict, and war. It is an instinct that has been coupled with a life-long interest in literature and art that expresses and describes the ravages of systematized violence: from Primo Levi, Tim O’Brien and Harper Lee to Maryse Condé, Alain Resnais, and Isabel Allende. It was first the memoirs from Holocaust survivors followed by the accounts of the military dictatorships in South America and then the testimony of the brutality of slavery in the Caribbean that have over time constructed my conviction in justice, freedom, and accountability, but also at the same time, for nunca más.

“Never again” is always associated with World War II, but in Colombia, never again continues to be called for even as Colombians continue to suffer and die every day due to ongoing violence. Our “armed conflict” is unique in the way that the categories of victims and victimizer are not always so neatly separated. It is as the writer Rodolfo Celis Serrano describes in his autobiographic short text on life in the Usme neighborhood of Bogotá: there are things that he did while living under the threat of violence that still bring him shame and guilt. Celis was displaced from his home, a victim of the armed groups that took over the territory, and yet he himself complicates the category of “victim” by highlighting his own guilt. In Colombia, we have to reckon with reintegrating combatants and civilians of all types into peaceful communal living, while at the same time trying to balance this with the pursuit of justice and accountability.

And there are so many Colombian thinkers, artists, and activists that have been working through the inherent paradoxes of prolonged systemic violence for years.

One of them was Javier Darío Restrepo, who I am currently reading. For my next log entry, I want to reflect on Restrepo’s writing along with the work of Jean Giono, another author who I also read and rediscovered this month.

Their writing has given me much to think about what peace means, as real action and not just a “utopian” concept. In their writing, I’ve found that same visceral rejection to war and violence that I feel—that war is senseless at its core, even with all the justifications that we try to dress it up with. In their writing, I’ve also confirmed that this rejection of war does not entail sacrificing strong convictions about rights and wrongs, it doesn’t equal apathy or “neutrality” in the face of cruelty, injustice, and inhumanity.

“El carácter del conflicto, su prolongación en el tiempo, la complejidad y multitud de los elementos en juego, el constante juego de la desinformación—que no es accidental sino parte de la táctica guerrera—, crean una atmósfera de confusión tal que la gente muere todos los días sin saber por qué muere”. – Javier Darío Restrepo, Pensamientos (p. 221)

« Il faut sinon se moquer, en tout cas se méfier des bâtisseurs d’avenir. Surtout quand pour battre l’avenir des hommes à naître, ils ont besoin de faire mourir des hommes vivants. » – Jean Giono, Refus d’obéissance (p. 14)

- Andrea

29.09.2024 // Wonderment at Kalopanagiotis

Paramytha, Cyprus ⬔

Only 24 hours ago we were there: tucked away in the tight valleys of the Troodos (Τρόοδος) mountains, traversing twists and turns under a brilliant blue sky and the gaze of tall pines. Villages hung from the mountainside, and one of these was Kalopanagiotis (Καλοπαναγιώτης).

Of the high highs and low lows that have characterized my first few days on Cyprus, Kalopanagiotis is literally and figuratively a very high high. The drive up from the southern coast into the mountains offers views that words do little justice to. Near Mount Olympus, the highest peak of the island, the view of the northern coast appears, and Cyprus suddenly feels small again, like when seen on a map for the first time. It is a unique feeling to reach a mountain peak and to be able see the physical constraints that the sea places on land. It’s so different from the huge, continental places I grew up in that felt boundless.

I first discovered this feeling of "boundedness" in Guadeloupe, which despite its very small size on the map felt bigger than Cyprus. I think it probably is, given the way maps distort landmasses. In any case, I still remember that feeling, on my first visit to Terre-de-Haut in the archipelago of Les Saintes, when I climbed up to the highest peak and realized that I could see the entire island from there, all around me. A few months later, I re-encountered "boundedness" in Saint Cloud. From the slopes of the Soufrière volcano, I looked out and down onto the coast on which I lived, walked, and worked everyday. While the view of the sea provides a sense of vastness that is familiar to me, seeing the long but limited coast so perfectly drawn out made the feeling of boundary visceral.

But back to Kalopanagiotis, which meant to dive back down into the earth after circling the peak of Mount Olympus. Kalopanagiotis hugs the curve of a valley that cradles a small creek lush with vegetation. Now, instead of looking down, I found myself looking up a lot, at the peaks, the sky, the buildings and streets above us. The awe of the mountain peak had given way to the intimacy of the valley.

Despite the smallness of the village, it felt like there were not enough hours in the day to stroll through its narrow roads and river paths, once, twice, thrice. Kalopanagiotis is penetrated by history, with its Byzantine artwork and archaeological remains of monasteries, baths, and water mills. At the same time, local businesses are vibrant and include a winery, artisanal stores, fusion restaurants and more. Nature, archaeology, art, and the culinary arts—I couldn’t ask for more.

But when I try to capture the wonderment that I felt, I am reminded how insufficient words often are. There is no list of attraction detailed enough to really capture that feeling.

I would have to resort to art, rather than a log entry (What’s the difference? Can’t anything be art? But there is a difference, I can feel that there is.), to piece together that joy of discovering someplace beautiful, new, and already nostalgic.

- Andrea

29.09.2024 // Pour-over | First attempt

Paramytha, Cyprus ⬔

Beans

Tesfaye Coffee from Ethiopia. Vendor lists notes of strong fruits and jasmine.

Equipment

- Coffee: Ethiopia Tesfaye, 20 grams, medium ground.

- Water: 320g tap water

- Equipment: kettle, pour-over brewer, filters, scale

Method

1. Rinse the filter, pour out the excess water

2. Pour 20g grounded coffee, shake gently to level.

3. Pour first 50g of water in a circular motion, wait 30 secs.

4. Pour second 150g in a circular motion, wait 10-20 secs.

5. Shake gently to level.

6. Pour last 120g, totaling 320g

7. Shake gently to level.

8. Wait for pour over to complete

Observations

- The filter flops over and is unstable, potentially hindering the water flow.

- Water was just beginning to boil before use.

Results

- Lack of aromatic profile, no smell.

- Andrea observed bitter tones.

- Marc observed overall delicate flavor with floral notes, not too strong.

Conclusions

The goal is to brew for coffee with less bitterness and more aroma. Variables we can tweak are:

- Temperature of the water.

- The tap water.

- The spiral pouring technique.

- The filter used.

- Altering ratio of water to coffee ground.

- The amount of pulses and the pauses between the pulses.

We also recognize that some of the limits are due to the equipment.

- Marc & Andrea

26.09.2024 // Halfway Across the World

Limassol, Cyprus ⬔

We arrived in Cyprus almost exactly one week ago. Today, I sit at a café in Limassol, looking out at the lively sunny street near the center of town, and I feel as if I had only just arrived. As if newly landed.

Like any change, moving always requires effort, usually new and unusual sorts of effort. After a lifetime of moving from here to there, I like to think that I have strategies in place to help me in these moments of transition. And yet, it can be hard, and it has been hard.

The countryside of a new country has special surprises, especially for city people, and I realize more and more that I am city person—despite my love for hiking and nature. Encountering sand flies for the first time, a drought for the third time this year, and challenges in transportation, all while coming down with a cold, is not too much fun. Even if we expected some challenges (like the transportation one), there's no way to sugarcoat the truth, it’s been tough.

I also realize how much I cherish self-sufficiency, which is to say my independence. Not being able to address challenges from the get-go due to feeling unwell and not knowing how things worked made me feel trapped.

And yet, things have slowly fallen into place, with some patience and initiatives to put things in order. Now, it feels like life is ready to begin again.

This experience made me reflect on some other challenging moves I've gone through, two of which were even more challenging. Moving to Paris, for one, and also Vieux-Fort in Guadeloupe (another island) tested me in more ways than one. Stockholm was also tough in the first three days, but overall, less tough than the first week of Paramytha. Even with those rough starts, I've yet to regret moving someplace new (even with new challenges that appear, like the COVID-19 pandemic while I was in Guadeloupe) and I hope this holds true for Paramytha, Limassol, and Cyprus generally.

- Andrea

22.09.2024 // Chautauqua

Paramytha, Cyprus ⬔

Currently, I am reading the book Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, and it is divided into several Chautauquas. Chautauquas began as part of a social movement during mid-20s America and they consisted of educational events full of "entertaining lectures, performances and/or concerts". The story of Zen And The Art Of Motorcycle Maintenance uses this concept to deliver philosophical insights in a way that is more entertaining to the reader, and uses, as you might guess, motorcycle maintenance to talk about what is the meaning of quality and why quality matters.

- Marc

20.09.2024 // Emacs, the Computing Environment

Paramytha, Cyprus ⬔

I love Emacs as a system, even if it is a bit slow and bloated. People joke that Emacs is a great OS that is missing a text editor. And well, while Emacs does not actually handle persistence, concurrency, virtualization, yadda yadda, which an OS normally should, it is certainly not just a text editor. I think of it as a computing environment.

Compared to Kakoune or Neovim that open in milliseconds, Emacs loads in seconds. Many features have noticeable delays that just feel like they should be smoother, and you wonder if there aren’t a few features that could be cut. But despite that, I think it contains so many interesting utilities and features that I just wish were available in regular Unix.

There is without a doubt a certain charm to Emacs. Here are some of the Emacs features that I would love to bake into Unix and terminal ecosystems:

- Ease of access to offline documentation. Info-pages get a bad rep, maybe in part because the keybindings are very Emacs specific, but it solves a real need. Because man-pages are meant to be terse and for reference, they can not contain everything necessary to provide good documentation.

- Everything can be linked and bookmarked. That means that if you have references scattered around different documents, you are able to very easily bring them together. For example, I have bookmarks to reference documentation, websites, emails, all accessible from a single place. In Org mode, I can have TODO items that link to specific parts of a code.

- Documents can be interactive. Together with

org-babelorhyperbole, you can create interactive media. For example, hyperbole can add a document full of commands you can run, so your documentation is interactive.org-babelcan enable you to to write documents with code-snippets in them so that you can evaluate them. - Variable pitch mode and image rendering. Variable pitch mode allows you to switch between a sans font and a mono-spaced font. This along with images makes for a much better reading experience when browsing the web.

- It can load images directly. There is a way to do so as well if your terminal emulator has sixel support, but this feature is not really used so often.

I would like to use a Unix terminal instead of a Lisp VM like Emacs, as I do prefer an ecosystem where you are not just bound to Lisp but can use whatever tool you want. In theory, a lot of what Emacs can do is feasible in Unix, but in practice the ecosystem is far behind. If you are like me (you basically live within your terminal), I find that you are better served by a system like Emacs.

- Marc

11.09.2024 // August Reads

Bogotá, Colombia ⬔

While we are now well into September, I wanted to take a moment to reflect on some memorable August reads, books that I still think about and will be thinking about for a while.

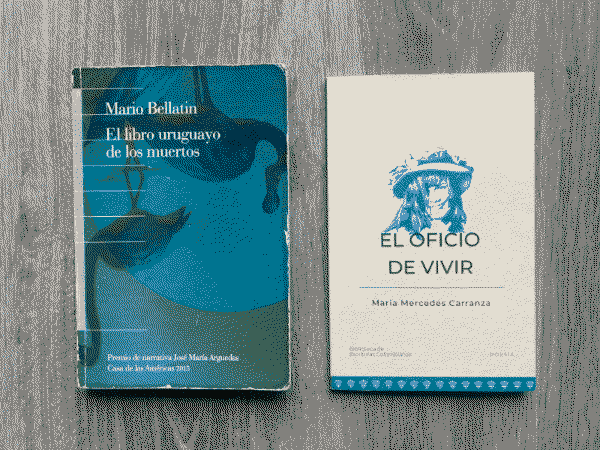

I read two books last month, one poetry and one prose (very unconventional prose, however).

El oficio de vivir, or (roughly) The craft/work of living, is a collection of poetry by María Mercedes Carranza. Compiled posthumously and prefaced by her daughter, the collection sinks, poem by poem, deeper into the despair that plagued Carranza, especially in her final years. Despair about aging, despair about Colombia’s endless violence, despair about injustice, meaninglessness, despair about despair. Death weighs heavy on almost every page. Her words manage to covey the hollowness of depression in a way that I have not seen captured in any other piece of writing (even books and memoirs about war or genocide). It is grim, very grim.

El libro uruguayo de los muertos, or The Uruguayan Book of the Dead, on the other hand was much less grim, despite of the title. It did take me a very long time to read. Along with García Márquez’s El otoño del patriarca, it might be one of the toughest books I’ve ever gone through. In short snippets destined to a mysterious correspondent, Mario Bellatin melds fact and fiction to speak about everything and anything. Some themes do stand out: writing, publishing, illness, death, family, truth, falsehood and mysticism. Like the Twirling Dervishes he describes, cyclical snippets of narrative appear, disappear, only to reappear later, the same or almost the same or altered incomprehensibly. Temporality is warped, contradictions appear, and, as a reader, offering resistance only makes the read more painful. At some point you just have to let go and let Bellatin take you on a trip that goes round and round. And in the end, I was left a bit dizzy.

El oficio de vivir was close to making it on my favorites list—it is a true work of art. But the art that resonates with me the most is that which peers into the void, but with defiance. There is a will to live and an affirmation of life, the renewal of life. With Carranza, we succumb to the void, even if the last poem of the collection offers a glimmer of hope.

Mario Bellatin’s Salon de belleza (Beauty Salon) is one of my favorite books, but I can’t say the same for El libro uruguayo de los muertos. There are very interesting ideas about the nature of truth and fiction, about the pain of creation, and about life, death and creation as cyclical. The unconventional form resonated with these themes, but maybe it went on for too long. But then again, watching Twirling Dervishes perform is fascinating, but it can also feel eternally long after a while. But isn’t that what we’re all after, eternity? Reading El libro uruguayo de los Muertos definitely felt like it took an eternity too, but maybe that's what Bellatin was trying to do—approach eternity, which also means to approach death.

Other Interesting August Reads

- “Programming is Forgetting: Toward a New Hacker Ethic”

- “The Betrayal of American Border Policy”

- “The Funeral: At a Loss” (recommend reading this only after watching Itami Juzo's film)

- Andrea

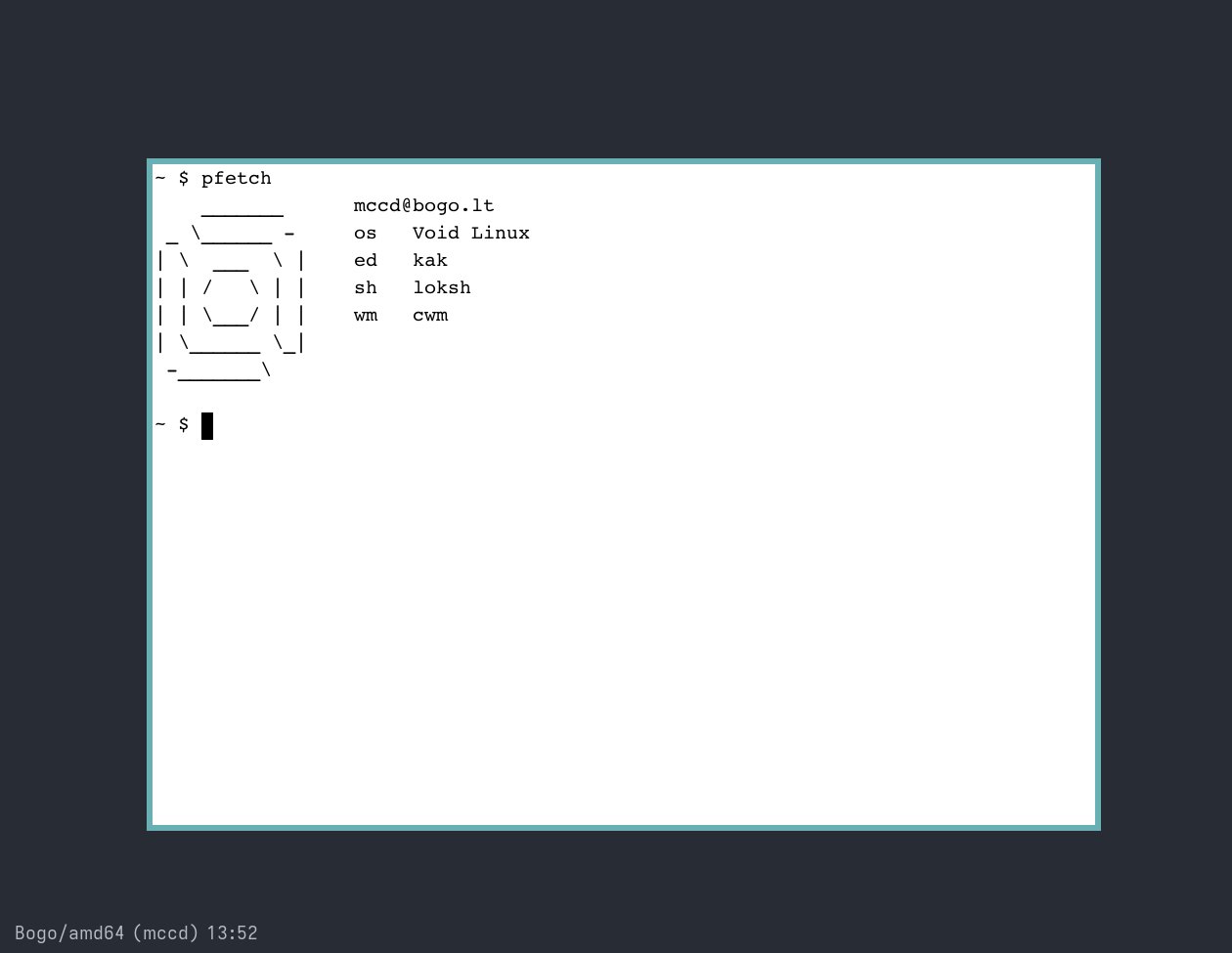

10.09.2024 // Laptop: Bogo

Bogotá, Colombia ⬔

Bogo is my Thinkpad T480s that has served as my primary laptop since 2019.

System Description:

- Kernel: 6.6.50_1

- OS: Void Linux

- Desktop: CWM

- Fonts: Iosevka Aile, Courier 10 Pitch

- Term: Urxvt

- Editor: Kakoune

- Shell: ksh

- Connection Manager: iwd

- Audio Manager: pulseaudio

- Battery:

ID-1: BAT0 charge: 41.9 Wh (91.7%) condition: 45.7/57.0 Wh (80.2%) - CPU: Intel Core i7-8650U

- CPU Speed (MHz):

avg: 593 min/max: 400/4200 cores: 1: 400 2: 780 3: 400 4: 400 5: 800 6: 764 7: 400 8: 800 - Graphics:

Intel UHD Graphics 620

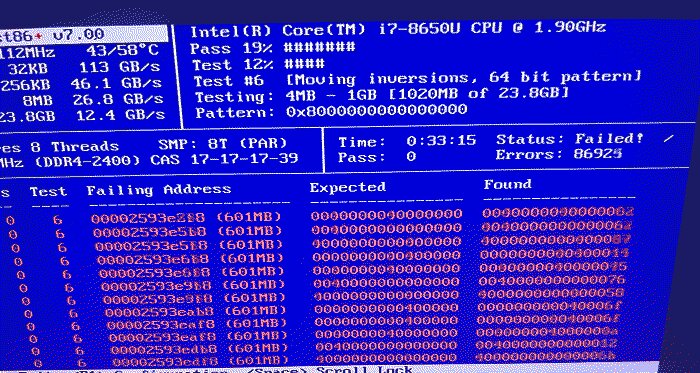

Bogo was serviced with a X1Y3 glass trackpad, new RAM and SSD after RAM reported faulty in 2024.

- Marc

09.09.2024 // Cloud Solutions Make It Hard to Measure Energy Usage

Bogotá, Colombia ⬔

Today, I continued my exploration into measuring energy usage for a server. To my dismay, I discovered that when running software within a VPS, measuring its energy usage becomes impossible. A VPS obscures the underlying hardware to protect other servers running on the same hardware. Theoretically, an attacker could use the energy data to perform side-channel attacks to extract private keys from other users, so there are good reasons to keep the data hidden in virtualized systems.

All the companies that I have worked for rely on VPSes and VMs, with no access to the underlying hardware. I imagine at this point it is pretty standard in the industry, which makes me think that few companies are able to measure their energy usage and understand the footprint of their backend.

It is unfortunate because sharing the hardware also means that we could leverage it more efficiently, and avoid over-provisioning hardware. At the same time, when you do not understand how much energy the software is using, it encourages wastefulness.

Related Reading: "Green Networking Metrics"

- Marc