Books | Reviews

10.09.2025 // Summer-Winter Reads: June, July, and August

Cape Town, South Africa ⬔

I have read and written less than I would have liked during the past three months. Not too unexpected, however, as it has been the part of the year in which I have traveled the most. After a month in Cape Town, I feel like I have some room for pause and reflection on the books that have accompanied me from Bath and London to the United States and now South Africa.

I realize now that my reading has been just as scattered as my physical presence: from a radio journalist's compilation of tales about the lives of Chinese women in the 80s and 90s to contemporary queer Latin American poetry and an academic analysis of the cultural impact of Ayn Rand. It has been interesting. So much so, that I do not really know where to begin.

Perhaps, I should begin at the beginning. And an important beginning for me is Jane Austen. Bidding adieu to Bath, I re-read Pride and Prejudice during my last few days in the UK. It happened spontaneously, or as spontaneous as it can be when at every corner I was reminded that it was the 250th anniversary of Austen's birth. Bath practically burst with Austen, and I eyed it all a bit skeptically. Maybe with a similar skepticism to that with which I approached Pride and Prejudice for the first time when I was in high school. However, Austen's eternally fresh and funny storytelling always manages to sweep away my reserve. With each re-reading, my appreciation only grows and I was pleased to have had the novel's company during the long hot nights of a London heatwave.

Some of my other reads this summer were less comforting, matching the anxious tone of the times, of degradation in all sense of the word. Mean Girl: Ayn Rand and the Culture of Greed by Lisa Duggan and The Good Women of China: Hidden Voices by Xinran are two non-fiction books that prompt reflection on how societies function and malfunction, and how this malfunctioning can profoundly hurt individuals, families, and communities. What ideas get to be influential and why? How do we displace harmful ideas and conventions?

The pessimism and anxiety that comes from ruminating on the world's biggest issues, some that perhaps seem unsurmountable, is one of the main themes of the other book that accompanied me on flights and train rides: A System So Magnificent It Is Blinding by Amanda Svensson. This big novel is full of quirky moving pieces, like a Murakami novel, but very Swedish and with less music. Faraway places, improbable images, coincidences that promise to be part of some big conspiracy. The three sibling protagonists try to make sense of a world that feels like it is going to pieces. In the end, I felt like this novel was an exercise in building suspense and anticipation only to purposefully disappoint in order to make a point. I appreciated the concept and the intent more than the novel itself, unfortunately. Not sure I would pick it up again, but I am glad to have read it.

In the midst of all of that, I stumbled into some poetry as well. Feeling a bit nostalgic for home, I picked up an anthology of queer Latin American poetry edited by the Argentine poet Leo Boix, as well as a newly published work by Boix. Within Hemisferio Cuir: An Anthology of Young Queer Latin American Poetry, I was pleased to discover poetry from across the region, including some countries that are less well represented on the global literary stage. These are the poems from the collection that stuck with me:

- "El agua de los sueños" de Flor Bárcenas Feria

- "Oda a Querelle de Brest" de Pablo Jofré

- "Una parra sube" de Paula Galíndez

- "Poetas enamoradas" de V. Andino Díaz

- "Cómo ser feliz siendo de Nicaragua" de Magaly Castillo

- "poema [post]umo" de Alejandra Rosa-Morales

- Andrea

15.08.2025 // Unearthing Gems

Cape Town, South Africa ⬔

While practising my Portuguese and going through an anthology of Brazilian literature a good friend gifted me many months ago, I discovered a three-page short story that dazzled me. Up until this point, I had read through the other excerpts and stories with a studious sort of interest, discovering new authors and literary styles. But encountering Machado de Assis' Um apólogo blew me away and made me think that the classics are the classics for a reason. Yes, lots of great art gets left out of "the canon," especially that of marginalized groups. I believe there are many more "classics" out there than those regularly taught in classrooms. Nonetheless, I understand why Machado is considered one of Brazil's greatest writers. It is not unmerited.

I wish I could write first lines as good as these:

"Era uma vez uma agulha que disse a um novêlo de linha: —Por que está você con êsse ar, tôda cheia de si, tôda enrolada, para fingir que vale alguma coisa neste mundo?"

To write a very good story about the rivalry between a sewing needle and a ball of thread is impressive. Machado adopts the conventions of the fable, even including a little lesson or moral at the end, but the story goes beyond the traditional fable and takes on an almost existential or absurd sense.

There have been times that as I writer I have wondered if what I am writing about is too silly or random. Machado's amazing little story about a humanized sewing kit is a necessary reminder that the skill and imagination of a writer can make any subject enthralling and thought-provoking.

Now, I really want to read Machado's Memórias Póstumas de Bras Cubas, which has been languishing in my mental "to-read" list for at least a decade.

- Andrea

16.06.2025 // Half a Year of Books (Part II)

Bath, England ⬔

From within one of Bath's most charming bookshops, I write the second half of my reflection on books read during the first half of 2025, perched on a wooden balcony laden with shelves, tables, books—overlooking even more books, as a well as smatterings of people chatting and enjoying each other's company. A reminder of what the world can be, at its best, even in the moments that feel heavy under the long shadow of violence. I conclude my overview in the company of books currently being read, wanting to be read, and those that inevitably I will never get the chance to read.

Some Surprises

One of the habits I have picked up on my travels is that of allowing chance and generosity to direct my reading list. I have come to learn that, in most places, readers have a tendency to set up little trading nooks of books. From the kaz à livres encountered while hitchhiking along one those steep winding Guadeloupean roads to the small stack of books sitting in the lobby of L'Alliance Française in Ipanema—new books often find me when I least expect it. Books that perhaps I imagined reading someday, others that I might have otherwise never made my way to.

One of this year's most interesting surprises came from the Joigny food market. Tucked into the side of one of the entrances, I noticed a bookshelf, improbable in a visual field peopled with the weekend's fresh produce and other agricultural products: leafy greens, cheeses, winter fruit, fish, honey, saucissons. The bookshelf was nonetheless a popular spot for the townspeople, many of whom paused there on their way in and out with their Saturday shopping. Intrigued, I leafed through all sorts of books, from cookbooks to thrillers, until something caught my eye: an early 20th century edition of Jean de La Fontaine's fables.

I was familiar with La Fontaine; his most well-known takes on classic fables, such as "The Hare and The Tortoise", are staples of French language classes. Which is to say, La Fontaine inhabited a corner of my brain associated clichés and easy moralism. Even so, the beauty of the little old book won over my prejudices, and I am glad it did.

Far from being the morality tales that I imagined them to me, La Fontaine's 17th century retelling of classic fables is riddled with contradiction, humor, rebellion, and more than a touch of existential angst. At times, the "protagonists" of the fable-poems can appear to embody straightforward moral principles, like the "hard-working" ant of the famous "The Grasshopper and The Ant". However, I found the ant to be portrayed as judgemental and almost cruel in its treatment of the grasshopper; an attitude that was explicitly condemned in some of the other fable-poems in the collection. I was left feeling unsure of La Fontaine's stances throughout. In one fable, craftiness is celebrated, in the next it is condemned as dishonest. I like to think that, perhaps, as La Fontaine re-read and re-imaged these classic fables, he was also intrigued by the contradictions that came to light. Perhaps, rather than handing out morals, his work actually highlights the fact that trying to extract straightforward lessons from life is impossible.

The biographical information provided in the book lets me entertain that hypothesis. La Fontaine lived during the reign of Louis XIV, the powerful Sun King, but led a life that feels uncannily modern. Exiled for going against the grain and having what was judged by the monarch to be a "dubious" morality, La Fontaine nonetheless succeeded as a poet and garnered enough support to live from his art. Almost atheistic before his time, but suddenly pious when faced with death, La Fontaine was self-disparaging, funny, lucid, and self-delusional in ways that feel very human. Rather than going around moralizing, I find that La Fontaine crafted beautiful poetry through which he reflected on what it means to live a good life. He also contributed to important discussions about power, art, governance, and education, but I'll stop myself here.

Thus far, there have been two more surprising reads this year. One also came from the Joigny market bookshelf, the play Athalie by Jean Racine. When I picked it up, my only expectation was to read a work by a "classic" French author that I had not read yet. I ended up enjoying a great play that posed some very pertinent questions about power, violence, and freedom (it was "softly" censored during Racine's lifetime, posthumously considered to be one of his greatest works). The second surprise thought-provoking book was a gift of sorts from a good friend, who suggested I read Don't Sleep, There Are Snakes: Life and Language in the Amazonian Jungle by the missionary-turned-linguist Daniel L. Everett.

Our Times

As it might be apparent from the last section, I cannot help but associate what I read with the challenges we face today—even if it's a poetry book about talking frogs and dogs from the 1700s. It is one of many reasons that I am particularly unreceptive to the assertions that studying literature is "useless".

As a result, I could have honestly featured many of the other books that I have read this year in this section: from Umberto Eco's depiction of socioeconomic inequality in The Name of the Rose to the questions raised by Tanizaki Jun'ichiro with In Praise of Shadows that foreshadow current debates on globalization and representation.

I chose to feature two works here that for different reasons touch on topics that are near and dear, Ce que c'est que l'exil by Victor Hugo and 10.000 horas en La Silla Vacía: Periodismo y poder en un nuevo mundo by Juanita León.

After reading Les Misérables during university, I developed a soft spot for Victor Hugo and his sense for over-blown grandiosity and drama. Hugo's style feels acutely that of another era, but many of his biggest concerns are timeless. The basic premise of Les Misérables, that of the injustice of condemning a man to forced labor for the hunger and misery he was born into, continues to resonate in global demands for greater equity and justice.

With Ce que c'est que l'exil, which roughly translates to The nature of exile, Hugo reveals the price that he had to pay for his activism as well as his opposition to the reign of Napoleon III. While I had been vaguely aware that Hugo had been, at some point, exiled to the islands in the English Channel, I initially processed this fact as historical trivia, without much thought. However, through this book, Hugo acutely transmits what it is like to be condemned to exile, persecution, spying, and harassment for 20 years. Beyond appreciating Hugo the literary legend, I felt that I approached Victor the man.

At the same time that I recognized and lamented the struggles Hugo described, reading Ce que c'est que l'exil ultimately gave me hope that the ideals for justice and peace that can feel hopelessly out of reach today could one day materialize. Among the "radical" ideas that Hugo was persecuted for in his time: his support for universal suffrage and public access to education, his opposition to slavery, domestic abuse, and tyranny. More than describing his own suffering, Hugo highlighted the importance of persistence in the fight for greater justice, and the key role of solidarity, even in moments that can feel so isolating.

There is a lot of talk of our contemporary collective disenchantment, of a vacuum left in the wake postmodernism that needs to be filled. It is a discussion that awakens all my skepticism, as it often leads to claims that as humans we essentially "need" religion. I won't go down this rabbit hole now, but I will recognize the need for a coming together that is constructive and empathetic. In my eyes, Hugo's romanesque writing (even with its flaws) shows a way. I was sad to find that there was no English translation for this text which, like with Carranza's poetry, made me once again entertain ideas of translation and dissemination.

Similarly, my other pick for this section is not available in English, as far as I know. 10.000 horas en La Silla Vacía: Periodismo y poder en un nuevo mundo is a reflection on contemporary journalism in Colombia written by Juanita León, the founder of one of the leading independent news outlets in the country, La Silla Vacía. In her book, León looks back on how it all started and how, despite all the challenges, La Silla has persisted as an independent outlet. This necessarily involves an overview of Colombia's recent economic and political history. Not only did I fill in some gaps in the understanding of our recent history, but León focuses a lot on identifying and describing the mechanics of power. Colombian society is incredibly conservative and hierarchical; Colombians have some of the worst prospects for social mobility in the Americas. From the outside, we all vaguely perceive the structures that keep power in place and concentrate it, but León allows the reader to peer within these machinations.

At the same time, León candidly reveals that to keep La Silla Vacía afloat she has to make use of all those social markers and contacts that are the key to getting anything done in Colombia. León must operate within the very system her outlet critiques, which generates tensions and difficult ethical dilemmas. I find her transparency around the logistic issues of keeping a media outlet running so important when thinking about how to create alternatives, as she did when she decided to launch an alternative to the big legacy media.

At a moment that violence is rising again in Colombia, in which it feels like the country is stuck in a hamster wheel of death, León's book provides precious understanding. This light that journalism, testimony, and research, all offer is vital to warding off the informational darkness that violence requires to thrive. One of the Colombian journalists that I admire the most, Javier Darío Restrepo, spoke widely about this during his lifetime. I reflected a bit on his writing last year while in Cyprus.

Other Interesting 2025 Reads

To conclude, some final books that prompted me to reflect on literary form and genre. From Sontag's essay in the form of a list to Shambroom's ekphrastic history-essay, these works serve as a reminder to imagine more.

- Duchamp's Last Day by Donald Shambroom

- L'exil et le royaume by Albert Camus

- L'homme qui plantait des arbres by Jean Giono

- Notes on 'Camp' by Susan Sontag

- Andrea

07.06.2025 // Half a Year of Books (Part I)

Bath, England ⬔

When I first posted the "August Reads" entry in 2024, I imagined ambitiously that every month I would upload a "review" of the books I read. Almost a year later, I would like to rescue that idea. There are so many interesting books that I have read and re-read since then, but I will restrict myself to some scattered reflections on the past half year of reading.

New Favorites

So far, this year's grand revelation is The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco (along with Camus' Le mythe de Sisyphe, but I am still working on it). In one novel, Eco managed to speak to my childhood love for detective novels, my teenage nerdiness for learning as much as possible about anything and everything (including medieval Europe), and my present concerns about the nature of truth and living with truth in an ever-changing world of difficulties and possibilities. The prose was poetic and funny, page turning and almost inscrutable. Timeless and present with a 12th century setting, it is a transcendental book that I hope will always keep me company.

Before The Name of the Rose, I started the year off with Italo Calvino's Invisible Cities, and it provoked a very different type of awe. While Eco (and Camus) read grandiose and monumental, in many ways, Invisible Cities is quiet, but powerfully so. It achieves timelessness in a very different way, too. Like Eco, Calvino places us in a historical past, that of the Silk Road, Marco Polo, and Kublai Khan. However, where Eco as a medievalist is relatively rigorous, Calvino writes loosely and a parallel dream world arises from the history he is inspired by. Fantastic city after fantastic city, I felt more and more drawn into the world Calvino pieced together, a world that uncannily drifted very close to home, every so often, especially in the moments that, at first glance, appeared to be the most dream-like.

I extend an "honorable mention" to In Praise of Shadows by Tanizaki Jun'ichirou, which I read in the French translation (Éloge de l'ombre). The beautiful long-winding sentences unfurled quietly into piercing insights, not only about the development of Japanese culture up to the 20th century, but also with regard to what it means to attribute and develop value judgements within a cultural context. What is beauty? What is goodness? Tanizaki presents a calculatingly messy train of thought that waxes poetic. It is essay-poetry, in a sense. At the same time, I could not fully embrace Éloge de l'ombre due to the lingering taste of an essentialism that felt almost deterministic. At a moment of rising insularity and nationalisms, I find the quest for "essences" troubling. There is a fine line that shapes the difference between understanding how aesthetics and ways of doing arise from culture, and prescribing a certain way of doing as essentially "Japanese". And while Tanizaki displays a degree of self-consciousness as to the development of cultural norms within specific contexts and circumstances, he also does not hesitate to issue very clear-cut assertions that read too much like givens or truths about what a group people is "essentially" like. Nonetheless, a book I look forward to revisiting.

Illuminations

I have read two illustrated works during these first six months of 2025, Jungle Nama: A Story of the Sunderban by Amitav Ghosh and Salman Toor, and Looking for Luddites by John Hewitt. Both books made me reflect on the interplay between text and visual arts, which I think is very pertinent at a time that many predict (and/or lament) that both will be mechanized away.

This was my second reading of Jungle Nama, which I bought from Araku, a coffee shop we frequented during our stay in Bengalore. Looking for Luddites was found at a magazine and stationary shop I am fond of in Bristol: Rova. In a way, I encountered both books as artefacts that caught my passing eye.

For many decades, the predominant mode of thought has placed illustration as subservient to the written word. And in a way, illustration could even be considered as a "threat" to the seriousness of a book. Are picture books perhaps not "real books"? Jungle Nama and Looking for Luddites demonstrate that it is not so (as do so many other brilliantly illustrated books, such as the Alice books). Illustrations here prove to be not merely decorative, but rather are as essential to the storytelling as the text. The unique perspective or "eye" of the illustrator (even in the case of Hewitt, who is also the writer) cannot be subtracted away.

It is interesting to think about these books together, what does the retelling of a Bengali myth about the Sunderban mangrove forest have to do with the retelling of the Luddites' uprising against industrialization in Northern England? So much, it turns out, as both little books explore the nature of human greed as well as the complex relationships between human settlement and the natural world. In both works, authors and illustrators look to the past to raise timeless concerns that are among the most urgent today due the generalized use of AI and the destruction of our ecosystems. In both works, the "expendability" of human life mirrors the "expendability" of ecosystems, animals, and all other forms of life.

A parting thought related to pertinence, I read Jungle Nama at the same moment that both India and Pakistan were, once again, at the brink of war. Authored by an Indian writer and illuminated by a Pakistani illustrator, the book stands as a powerful contrast to war, illustrating what could be possible by coming together instead.

Reconsiderations

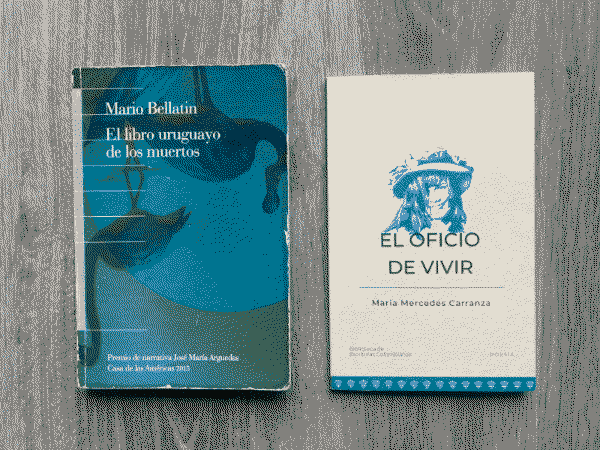

I have recently re-read two books of Latin American poetry, the Chilean poet Alejandro Zambra's Mudanza and María Mercedes Carranza's El oficio de vivir, the latter of which I wrote about for the original August Reads entry. I bought both books at the Bogotá Book Fair (FILBO) in 2024, and I picked them up again when I was feeling nostalgic about not being at FILBO this year.

First, I realized that I enjoyed both books more on the second read, which confirms by experience the well-known adage that good poetry must be re-read. In a sense, this reencounter with Zambra and Carranza is part of a multi-year reconciliation with poetry that first begun with Louise Glück. I had initially failed to connect with poetry, despite my love for reading, and I then struggled with it as a university student after the "Poetry 101" teaching assistant took great pleasure in announcing that the course was meant to "weed out" students from the English major. I survived the course, but ultimately chose not to major in English.

I had already appreciated Carranza's work on my first read, however, I couldn't quite count it among my favorites because I found the collection's bleakness to weigh too heavy. Carranza masterfully conveyed the hollow feelings of depression, and it was almost too much to bear. On a second read, however, my initial reticence has given way. The shock of encountering Carranza's profound listlessness and melancholy has subsided, and I felt like this time I could better perceive the beauty she crafted from the shadows. Despite of everything, glimmers of life shone through the despair and with the despair. It is a special book, compiled by Carranza's daughter with a lot of thought and care. I wish Carranza's poetry could be better known outside of Colombia. (And I wish I could translate it.)

My thoughts have strayed far, as usual, so I will continue my 2025 book reflection in a second entry.

Other Interesting 2025 Reads

- "The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House"

- "Permacomputing Aesthetics: Potential and Limits of Constraints in Computational Art, Design and Culture"

- Andrea

11.09.2024 // August Reads

Bogotá, Colombia ⬔

While we are now well into September, I wanted to take a moment to reflect on some memorable August reads, books that I still think about and will be thinking about for a while.

I read two books last month, one poetry and one prose (very unconventional prose, however).

El oficio de vivir, or (roughly) The craft/work of living, is a collection of poetry by María Mercedes Carranza. Compiled posthumously and prefaced by her daughter, the collection sinks, poem by poem, deeper into the despair that plagued Carranza, especially in her final years. Despair about aging, despair about Colombia’s endless violence, despair about injustice, meaninglessness, despair about despair. Death weighs heavy on almost every page. Her words manage to covey the hollowness of depression in a way that I have not seen captured in any other piece of writing (even books and memoirs about war or genocide). It is grim, very grim.

El libro uruguayo de los muertos, or The Uruguayan Book of the Dead, on the other hand was much less grim, despite of the title. It did take me a very long time to read. Along with García Márquez’s El otoño del patriarca, it might be one of the toughest books I’ve ever gone through. In short snippets destined to a mysterious correspondent, Mario Bellatin melds fact and fiction to speak about everything and anything. Some themes do stand out: writing, publishing, illness, death, family, truth, falsehood and mysticism. Like the Twirling Dervishes he describes, cyclical snippets of narrative appear, disappear, only to reappear later, the same or almost the same or altered incomprehensibly. Temporality is warped, contradictions appear, and, as a reader, offering resistance only makes the read more painful. At some point you just have to let go and let Bellatin take you on a trip that goes round and round. And in the end, I was left a bit dizzy.

El oficio de vivir was close to making it on my favorites list—it is a true work of art. But the art that resonates with me the most is that which peers into the void, but with defiance. There is a will to live and an affirmation of life, the renewal of life. With Carranza, we succumb to the void, even if the last poem of the collection offers a glimmer of hope.

Mario Bellatin’s Salon de belleza (Beauty Salon) is one of my favorite books, but I can’t say the same for El libro uruguayo de los muertos. There are very interesting ideas about the nature of truth and fiction, about the pain of creation, and about life, death and creation as cyclical. The unconventional form resonated with these themes, but maybe it went on for too long. But then again, watching Twirling Dervishes perform is fascinating, but it can also feel eternally long after a while. But isn’t that what we’re all after, eternity? Reading El libro uruguayo de los Muertos definitely felt like it took an eternity too, but maybe that's what Bellatin was trying to do—approach eternity, which also means to approach death.

Other Interesting August Reads

- “Programming is Forgetting: Toward a New Hacker Ethic”

- “The Betrayal of American Border Policy”

- “The Funeral: At a Loss” (recommend reading this only after watching Itami Juzo's film)

- Andrea