Books

Log Entries

08.02.2026 // The Machine Stops

Valencia, Spain ⬔

"Imagine, if you can, a small room, hexagonal in shape, like the cell of a bee. It is lighted neither by window nor by lamp, yet it is filled with a soft radiance. There are no apertures for ventilation, yet the air is fresh. There are no musical instruments, and yet, at the moment that my meditation opens, this room is throbbing with melodious sounds."

During the first week of February, Marc and I read E.M. Forster's "The Machine Stops" a short work of science fiction from 1909 that imagines a future in which humans now live in isolation, each individual buried away in their own room. Not by force, there are no locks in Forster's techno-dystopia. But, why bother moving when everything can be brought to you by the touch of a button? Food, music, medicine, the voice and image of a friend or child half-way across the Earth. What Forster describes resembles our present much too closely for comfort, even if our detachment from nature is not so complete and perhaps can never be. Still, the droning of Forster's all-encompassing Machine echoes the droning of the voracious data centers mushrooming all over the globe. And even more, Forster is able to foresee the development of a parasitic tech-human relationship, in which technology is no longer a tool to foster connections, improve efficiency, or obtain knowledge. No, to perpetuate itself, the Machine depends on people being incapable of independent decision-making and action. It actively fosters dependencies that leave humans at the mercy of the functioning of a technology they are no longer capable of understanding, nor fixing once it begins to break down.

We collected some of our favorite quotes from the text, which speak to the malaise felt by many now, in the face of numerous efforts to convince us to outsource critical thought and sense of responsibility, which in turn lessens our capacity to make informed and meaningful decisions.

"For a moment Vashti felt lonely. Then she generated the light, and the sight of her room, flooded with radiance and studded with electric buttons, revived her. There were buttons and switches everywhere--buttons to call for food for music, for clothing. [...] There was the button that produced literature, and there were of course the buttons by which she communicated with her friends. The room, though it contained nothing, was in touch with all that she cared for in the world."

"She made the room dark and slept; she awoke and made the room light; she ate and exchanged ideas with her friends, and listened to music and attended lectures; she made the room dark and slept. Above her, beneath her, and around her, the Machine hummed eternally; she did not notice the noise, for she had been born with it in her ears. The earth, carrying her, hummed as it sped through silence, turning her now to the invisible sun, now to the invisible stars. She awoke and made the room light."

"Here I am. I have had the most terrible journey and greatly retarded the development of my soul. It is not worth it, Kuno, it is not worth it. My time is too precious. The sunlight almost touched me, and I have met with the rudest people. I can only stop a few minutes. Say what you want to say, and then I must return."

"I am most advanced. I don't think you irreligious, for there is no such thing as religion left. All the fear and superstition that existed once have been destroyed by the Machine."

"Cannot you see, cannot all you lecturers see, that it is we that are dying, and that down here the only thing that really lives in the Machine? We created the Machine, to do our will, but we cannot make it do our will now. It has robbed us of the sense of space and of the sense of touch, it has blurred every human relation and narrowed down love to a carnal act, it has paralysed our bodies and our wills, and now it compels us to worship it."

"To such a state of affairs it is convenient to give the name of progress. No one confessed the Machine was out of hand. Year by year it was served with increased efficiency and decreased intelligence. The better a man knew his own duties upon it, the less he understood the duties of his neighbour, and in all the world there was not one who understood the monster as a whole. [...] But Humanity, in its desire for comfort, had over−reached itself. It had exploited the riches of nature too far. Quietly and complacently, it was sinking into decadence, and progress had come to mean the progress of the Machine."

- Andrea & Marc

22.01.2026 // Hasta pronto, Madrid

Valencia, Spain ⬔

Madrid melts into the dark foggy dawn as we pull away from the city aboard a high speed train. Soon the earth will appear reddish, fields of crops will rise from the crumbling slopes, and thin wispy wind turbines will just faintly emerge from the milky daylight, like the ghosts of the windmills Don Quixote might have slain in battle. And then, we will have left Castilla behind.

- Andrea

27.11.2025 // An Anthology of Brazilian Literature

Rabat, Morocco ⬔

Between October and now, I have read a couple of really great books and I have been meaning to write about them, but I think I will give up on the monthly review structure. I should really just write about a book when I am excited to do so, otherwise it becomes a bit of a chore. There are also some books that take a while to digest, like Albert Camus' The Myth of Sisyphus, which in many ways I am always writing about nowadays.

Something that is a bit easier to put on paper is a list of the wonderful stories that I encountered in an old anthology of Brazilian literature. I already dedicated one entry to a Machado de Assis story that really delighted me. I also mentioned Rubem Braga at some point. Now, here is the full list of the stories and authors that have stayed with me long after completing the whole book:

- "Um apólogo" de Machado de Assis

- "Festa" de Graciliano Ramos

- "História do Carnaval" de Jorge Amado

- "As mãos de meu filho" de Érico Veríssimo

- "Circo de coelhinhos" de Marques Rebêlo

- "Brinquedos incendiados" de Cecília Meireles

- "Gato, gato, gato" de Otto Lara Resende

- "Céu limpo" de Eduardo Campos

- "A aranha" de Orígenes Lessa

- "Uma vela para Dario" de Dalton Trevisan

And as a bonus...

Some other September + October Reads

- "Charulata: 'Calm Without, Fire Within'" by Philip Kemp

- "Patricia Lockwood Goes Viral" by Alexandra Schwartz

- "Highjump as Afrofuturism" by Gustav Parker Hibbett

- "Reading the Greeks Under a Blanket of Blue" by William Coleman

- "Fallen Fruit" by Don Mattera

- "When the Montuno Hits in Hong Kong: My Journey into Canton Mambo" by Gia Fu

- Andrea

19.10.2025 // What is Art?

Cape Town, South Africa ⬔

Lately, I have been thinking that, while good art often uncovers what is hidden, allowing us to see lucidly across large spans of time and space, the short-form clips of our age seem to instead obscure our sight.

Take, for instance, the "tradwife" trend on TikTok and Instagram. There is perhaps no more powerful antidote to the digital mirage of seemingly young, healthy, and manicured women endlessly showing off pampered babies and sponsored cleaning products, than the short story collection I recently finished reading. In Banu Mushtaq's Heart Lamp, a young housewife cries out to her husband (and to us all): "Others are not even married at my age. But I am already an old woman [...] My back is broken. These children, the home, samsara—do I have even a minute of free time? If I bear one child per year, what will I become? Don't you want me to live long enough to be a mother to these children at least?"

- Andrea

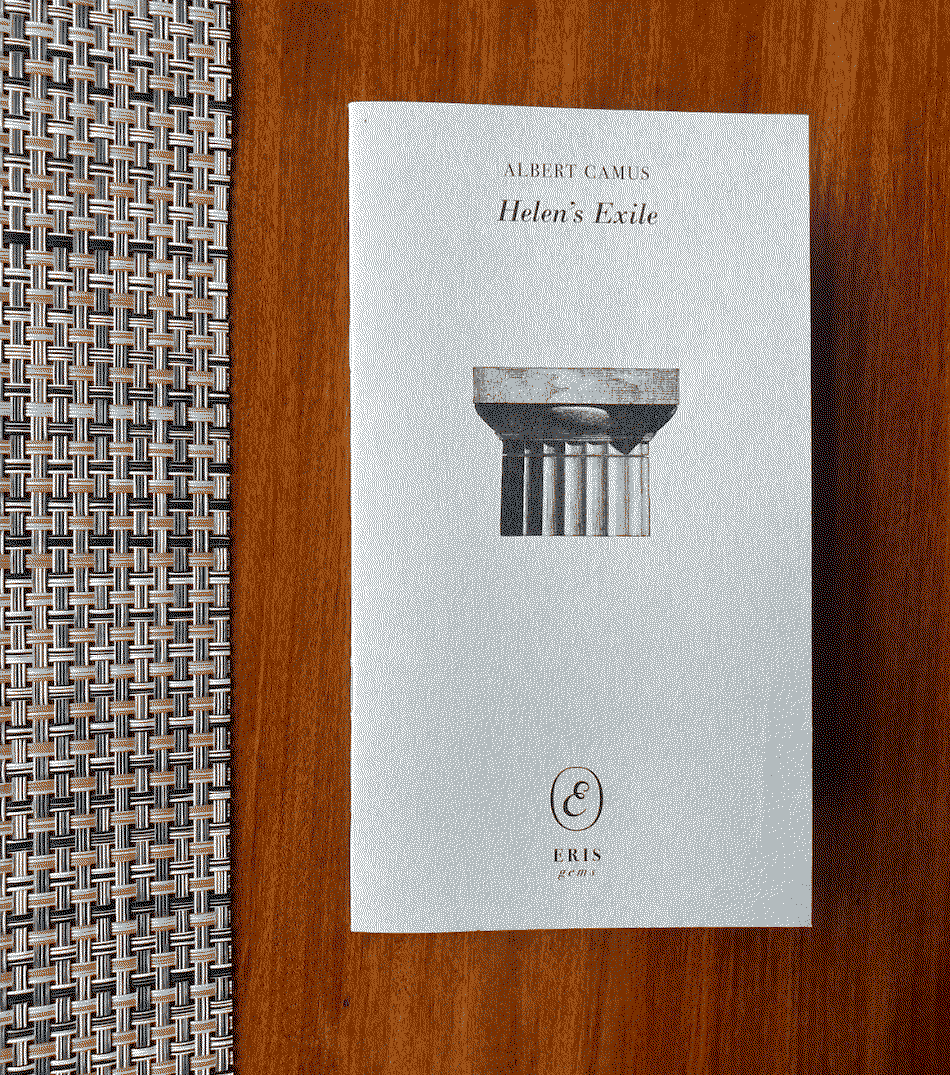

01.10.2025 // Helen's Exile

Cape Town, South Africa ⬔

After an early start to the day and to the month of October, we sat down with one of the essays of Albert Camus, "Helen's Exile". It proved to be especially lovely, melancholic and thought-provoking on a grey rainy day like today, and Camus' literary flair is always awe inspiring. We picked out a few of our favourite quotes, some of which can make confronting current events feel less lonely, and some of which speak to some of the other reflections posted on Comma Directory recently.

"Our Europe [...] off in the pursuit of totality is the child of disproportion."

"In her madness she extends the eternal limits, and at that very moment dark Erinyes fall upon her and tear her to pieces. Nemesis, the goddess of measure and not of revenge, keeps watch. All those who overstep the limit are pitilessly punished by her."

"In a drunken sky we light up the suns we want. But nonetheless the boundaries exist, and we know it."

"In our wildest aberrations we dream of an equilibrium we have left behind, which we naively expect to find at the end of our errors."

"We, too, have conquered, moved boundaries, mastered heaven and earth. Our reason has driven all away. Alone at last, we end up by ruling over a desert."

"Whereas the Greeks gave to will the boundaries of reason, we have come to put the will's impulse in the very centre of reason, which has, as a result, become deadly."

"Nature is still there, however. She contrasts her calm skies and her reasons with the madness of men. Until the atom too catches fire and history ends in the triumph of reason and the agony of the species."

"But the Greeks never said that the limit could not be overstepped. They said it existed and that whoever dared to exceed it was mercilessly struck down. Nothing in present history can contradict them."

"The historical spirit and the artist both want to remake the world. But the artist, through an obligation of his nature, knows his limits, which the historical spirit fails to recognise. This is why the latter's aim is tyranny whereas the former's passion is freedom."

"[Our era] wants to transfigure the world before having exhausted it, to set it to rights before having understood it."

"Whatever it may say, our era is deserting this world."

"Yet what a temptation, at certain moments, to turn one's back on this bleak, fleshless world! But this time is ours, and we cannot live hating ourselves."

"Admission of ignorance, rejection of fanaticism, the limits of the world and of man, the beloved face, and finally beauty—this is where we shall be on the side of the Greeks."

- Andrea & Marc

24.09.2025 // Echoes

Cape Town, South Africa ⬔

One of the benefits of reading widely and constantly is that the opportunities for enlightening coincidences multiply. A line from Rubem Braga's "O Motorista 8-100" suddenly echoes with the writing of Camus. I listen to a lecture on Jane Austen's personal letters and think of Banu Mushtaq's short stories. I write about an encounter with a dying bird on the sidewalk, I read Caetano W. Galindo's Lia and encounter a scene in which the protagonist, Lia, encounters a dead bird on the sidewalk. Nothing is original, but everything is. This does not discourage me. Ideas repeat, but never exactly in the same way. It testifies to the common experiences that bind living beings together, and it also speaks to individualities that are irreplaceable.

- Andrea

10.09.2025 // Summer-Winter Reads: June, July, and August

Cape Town, South Africa ⬔

I have read and written less than I would have liked during the past three months. Not too unexpected, however, as it has been the part of the year in which I have traveled the most. After a month in Cape Town, I feel like I have some room for pause and reflection on the books that have accompanied me from Bath and London to the United States and now South Africa.

I realize now that my reading has been just as scattered as my physical presence: from a radio journalist's compilation of tales about the lives of Chinese women in the 80s and 90s to contemporary queer Latin American poetry and an academic analysis of the cultural impact of Ayn Rand. It has been interesting. So much so, that I do not really know where to begin.

Perhaps, I should begin at the beginning. And an important beginning for me is Jane Austen. Bidding adieu to Bath, I re-read Pride and Prejudice during my last few days in the UK. It happened spontaneously, or as spontaneous as it can be when at every corner I was reminded that it was the 250th anniversary of Austen's birth. Bath practically burst with Austen, and I eyed it all a bit skeptically. Maybe with a similar skepticism to that with which I approached Pride and Prejudice for the first time when I was in high school. However, Austen's eternally fresh and funny storytelling always manages to sweep away my reserve. With each re-reading, my appreciation only grows and I was pleased to have had the novel's company during the long hot nights of a London heatwave.

Some of my other reads this summer were less comforting, matching the anxious tone of the times, of degradation in all sense of the word. Mean Girl: Ayn Rand and the Culture of Greed by Lisa Duggan and The Good Women of China: Hidden Voices by Xinran are two non-fiction books that prompt reflection on how societies function and malfunction, and how this malfunctioning can profoundly hurt individuals, families, and communities. What ideas get to be influential and why? How do we displace harmful ideas and conventions?

The pessimism and anxiety that comes from ruminating on the world's biggest issues, some that perhaps seem unsurmountable, is one of the main themes of the other book that accompanied me on flights and train rides: A System So Magnificent It Is Blinding by Amanda Svensson. This big novel is full of quirky moving pieces, like a Murakami novel, but very Swedish and with less music. Faraway places, improbable images, coincidences that promise to be part of some big conspiracy. The three sibling protagonists try to make sense of a world that feels like it is going to pieces. In the end, I felt like this novel was an exercise in building suspense and anticipation only to purposefully disappoint in order to make a point. I appreciated the concept and the intent more than the novel itself, unfortunately. Not sure I would pick it up again, but I am glad to have read it.

In the midst of all of that, I stumbled into some poetry as well. Feeling a bit nostalgic for home, I picked up an anthology of queer Latin American poetry edited by the Argentine poet Leo Boix, as well as a newly published work by Boix. Within Hemisferio Cuir: An Anthology of Young Queer Latin American Poetry, I was pleased to discover poetry from across the region, including some countries that are less well represented on the global literary stage. These are the poems from the collection that stuck with me:

- "El agua de los sueños" de Flor Bárcenas Feria

- "Oda a Querelle de Brest" de Pablo Jofré

- "Una parra sube" de Paula Galíndez

- "Poetas enamoradas" de V. Andino Díaz

- "Cómo ser feliz siendo de Nicaragua" de Magaly Castillo

- "poema [post]umo" de Alejandra Rosa-Morales

- Andrea

15.08.2025 // Unearthing Gems

Cape Town, South Africa ⬔

While practising my Portuguese and going through an anthology of Brazilian literature a good friend gifted me many months ago, I discovered a three-page short story that dazzled me. Up until this point, I had read through the other excerpts and stories with a studious sort of interest, discovering new authors and literary styles. But encountering Machado de Assis' Um apólogo blew me away and made me think that the classics are the classics for a reason. Yes, lots of great art gets left out of "the canon," especially that of marginalized groups. I believe there are many more "classics" out there than those regularly taught in classrooms. Nonetheless, I understand why Machado is considered one of Brazil's greatest writers. It is not unmerited.

I wish I could write first lines as good as these:

"Era uma vez uma agulha que disse a um novêlo de linha: —Por que está você con êsse ar, tôda cheia de si, tôda enrolada, para fingir que vale alguma coisa neste mundo?"

To write a very good story about the rivalry between a sewing needle and a ball of thread is impressive. Machado adopts the conventions of the fable, even including a little lesson or moral at the end, but the story goes beyond the traditional fable and takes on an almost existential or absurd sense.

There have been times that as I writer I have wondered if what I am writing about is too silly or random. Machado's amazing little story about a humanized sewing kit is a necessary reminder that the skill and imagination of a writer can make any subject enthralling and thought-provoking.

Now, I really want to read Machado's Memórias Póstumas de Bras Cubas, which has been languishing in my mental "to-read" list for at least a decade.

- Andrea

16.06.2025 // Half a Year of Books (Part II)

Bath, England ⬔

From within one of Bath's most charming bookshops, I write the second half of my reflection on books read during the first half of 2025, perched on a wooden balcony laden with shelves, tables, books—overlooking even more books, as a well as smatterings of people chatting and enjoying each other's company. A reminder of what the world can be, at its best, even in the moments that feel heavy under the long shadow of violence. I conclude my overview in the company of books currently being read, wanting to be read, and those that inevitably I will never get the chance to read.

Some Surprises

One of the habits I have picked up on my travels is that of allowing chance and generosity to direct my reading list. I have come to learn that, in most places, readers have a tendency to set up little trading nooks of books. From the kaz à livres encountered while hitchhiking along one those steep winding Guadeloupean roads to the small stack of books sitting in the lobby of L'Alliance Française in Ipanema—new books often find me when I least expect it. Books that perhaps I imagined reading someday, others that I might have otherwise never made my way to.

One of this year's most interesting surprises came from the Joigny food market. Tucked into the side of one of the entrances, I noticed a bookshelf, improbable in a visual field peopled with the weekend's fresh produce and other agricultural products: leafy greens, cheeses, winter fruit, fish, honey, saucissons. The bookshelf was nonetheless a popular spot for the townspeople, many of whom paused there on their way in and out with their Saturday shopping. Intrigued, I leafed through all sorts of books, from cookbooks to thrillers, until something caught my eye: an early 20th century edition of Jean de La Fontaine's fables.

I was familiar with La Fontaine; his most well-known takes on classic fables, such as "The Hare and The Tortoise", are staples of French language classes. Which is to say, La Fontaine inhabited a corner of my brain associated clichés and easy moralism. Even so, the beauty of the little old book won over my prejudices, and I am glad it did.

Far from being the morality tales that I imagined them to me, La Fontaine's 17th century retelling of classic fables is riddled with contradiction, humor, rebellion, and more than a touch of existential angst. At times, the "protagonists" of the fable-poems can appear to embody straightforward moral principles, like the "hard-working" ant of the famous "The Grasshopper and The Ant". However, I found the ant to be portrayed as judgemental and almost cruel in its treatment of the grasshopper; an attitude that was explicitly condemned in some of the other fable-poems in the collection. I was left feeling unsure of La Fontaine's stances throughout. In one fable, craftiness is celebrated, in the next it is condemned as dishonest. I like to think that, perhaps, as La Fontaine re-read and re-imaged these classic fables, he was also intrigued by the contradictions that came to light. Perhaps, rather than handing out morals, his work actually highlights the fact that trying to extract straightforward lessons from life is impossible.

The biographical information provided in the book lets me entertain that hypothesis. La Fontaine lived during the reign of Louis XIV, the powerful Sun King, but led a life that feels uncannily modern. Exiled for going against the grain and having what was judged by the monarch to be a "dubious" morality, La Fontaine nonetheless succeeded as a poet and garnered enough support to live from his art. Almost atheistic before his time, but suddenly pious when faced with death, La Fontaine was self-disparaging, funny, lucid, and self-delusional in ways that feel very human. Rather than going around moralizing, I find that La Fontaine crafted beautiful poetry through which he reflected on what it means to live a good life. He also contributed to important discussions about power, art, governance, and education, but I'll stop myself here.

Thus far, there have been two more surprising reads this year. One also came from the Joigny market bookshelf, the play Athalie by Jean Racine. When I picked it up, my only expectation was to read a work by a "classic" French author that I had not read yet. I ended up enjoying a great play that posed some very pertinent questions about power, violence, and freedom (it was "softly" censored during Racine's lifetime, posthumously considered to be one of his greatest works). The second surprise thought-provoking book was a gift of sorts from a good friend, who suggested I read Don't Sleep, There Are Snakes: Life and Language in the Amazonian Jungle by the missionary-turned-linguist Daniel L. Everett.

Our Times

As it might be apparent from the last section, I cannot help but associate what I read with the challenges we face today—even if it's a poetry book about talking frogs and dogs from the 1700s. It is one of many reasons that I am particularly unreceptive to the assertions that studying literature is "useless".

As a result, I could have honestly featured many of the other books that I have read this year in this section: from Umberto Eco's depiction of socioeconomic inequality in The Name of the Rose to the questions raised by Tanizaki Jun'ichiro with In Praise of Shadows that foreshadow current debates on globalization and representation.

I chose to feature two works here that for different reasons touch on topics that are near and dear, Ce que c'est que l'exil by Victor Hugo and 10.000 horas en La Silla Vacía: Periodismo y poder en un nuevo mundo by Juanita León.

After reading Les Misérables during university, I developed a soft spot for Victor Hugo and his sense for over-blown grandiosity and drama. Hugo's style feels acutely that of another era, but many of his biggest concerns are timeless. The basic premise of Les Misérables, that of the injustice of condemning a man to forced labor for the hunger and misery he was born into, continues to resonate in global demands for greater equity and justice.

With Ce que c'est que l'exil, which roughly translates to The nature of exile, Hugo reveals the price that he had to pay for his activism as well as his opposition to the reign of Napoleon III. While I had been vaguely aware that Hugo had been, at some point, exiled to the islands in the English Channel, I initially processed this fact as historical trivia, without much thought. However, through this book, Hugo acutely transmits what it is like to be condemned to exile, persecution, spying, and harassment for 20 years. Beyond appreciating Hugo the literary legend, I felt that I approached Victor the man.

At the same time that I recognized and lamented the struggles Hugo described, reading Ce que c'est que l'exil ultimately gave me hope that the ideals for justice and peace that can feel hopelessly out of reach today could one day materialize. Among the "radical" ideas that Hugo was persecuted for in his time: his support for universal suffrage and public access to education, his opposition to slavery, domestic abuse, and tyranny. More than describing his own suffering, Hugo highlighted the importance of persistence in the fight for greater justice, and the key role of solidarity, even in moments that can feel so isolating.

There is a lot of talk of our contemporary collective disenchantment, of a vacuum left in the wake postmodernism that needs to be filled. It is a discussion that awakens all my skepticism, as it often leads to claims that as humans we essentially "need" religion. I won't go down this rabbit hole now, but I will recognize the need for a coming together that is constructive and empathetic. In my eyes, Hugo's romanesque writing (even with its flaws) shows a way. I was sad to find that there was no English translation for this text which, like with Carranza's poetry, made me once again entertain ideas of translation and dissemination.

Similarly, my other pick for this section is not available in English, as far as I know. 10.000 horas en La Silla Vacía: Periodismo y poder en un nuevo mundo is a reflection on contemporary journalism in Colombia written by Juanita León, the founder of one of the leading independent news outlets in the country, La Silla Vacía. In her book, León looks back on how it all started and how, despite all the challenges, La Silla has persisted as an independent outlet. This necessarily involves an overview of Colombia's recent economic and political history. Not only did I fill in some gaps in the understanding of our recent history, but León focuses a lot on identifying and describing the mechanics of power. Colombian society is incredibly conservative and hierarchical; Colombians have some of the worst prospects for social mobility in the Americas. From the outside, we all vaguely perceive the structures that keep power in place and concentrate it, but León allows the reader to peer within these machinations.

At the same time, León candidly reveals that to keep La Silla Vacía afloat she has to make use of all those social markers and contacts that are the key to getting anything done in Colombia. León must operate within the very system her outlet critiques, which generates tensions and difficult ethical dilemmas. I find her transparency around the logistic issues of keeping a media outlet running so important when thinking about how to create alternatives, as she did when she decided to launch an alternative to the big legacy media.

At a moment that violence is rising again in Colombia, in which it feels like the country is stuck in a hamster wheel of death, León's book provides precious understanding. This light that journalism, testimony, and research, all offer is vital to warding off the informational darkness that violence requires to thrive. One of the Colombian journalists that I admire the most, Javier Darío Restrepo, spoke widely about this during his lifetime. I reflected a bit on his writing last year while in Cyprus.

Other Interesting 2025 Reads

To conclude, some final books that prompted me to reflect on literary form and genre. From Sontag's essay in the form of a list to Shambroom's ekphrastic history-essay, these works serve as a reminder to imagine more.

- Duchamp's Last Day by Donald Shambroom

- L'exil et le royaume by Albert Camus

- L'homme qui plantait des arbres by Jean Giono

- Notes on 'Camp' by Susan Sontag

- Andrea

07.06.2025 // Half a Year of Books (Part I)

Bath, England ⬔

When I first posted the "August Reads" entry in 2024, I imagined ambitiously that every month I would upload a "review" of the books I read. Almost a year later, I would like to rescue that idea. There are so many interesting books that I have read and re-read since then, but I will restrict myself to some scattered reflections on the past half year of reading.

New Favorites

So far, this year's grand revelation is The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco (along with Camus' Le mythe de Sisyphe, but I am still working on it). In one novel, Eco managed to speak to my childhood love for detective novels, my teenage nerdiness for learning as much as possible about anything and everything (including medieval Europe), and my present concerns about the nature of truth and living with truth in an ever-changing world of difficulties and possibilities. The prose was poetic and funny, page turning and almost inscrutable. Timeless and present with a 12th century setting, it is a transcendental book that I hope will always keep me company.

Before The Name of the Rose, I started the year off with Italo Calvino's Invisible Cities, and it provoked a very different type of awe. While Eco (and Camus) read grandiose and monumental, in many ways, Invisible Cities is quiet, but powerfully so. It achieves timelessness in a very different way, too. Like Eco, Calvino places us in a historical past, that of the Silk Road, Marco Polo, and Kublai Khan. However, where Eco as a medievalist is relatively rigorous, Calvino writes loosely and a parallel dream world arises from the history he is inspired by. Fantastic city after fantastic city, I felt more and more drawn into the world Calvino pieced together, a world that uncannily drifted very close to home, every so often, especially in the moments that, at first glance, appeared to be the most dream-like.

I extend an "honorable mention" to In Praise of Shadows by Tanizaki Jun'ichirou, which I read in the French translation (Éloge de l'ombre). The beautiful long-winding sentences unfurled quietly into piercing insights, not only about the development of Japanese culture up to the 20th century, but also with regard to what it means to attribute and develop value judgements within a cultural context. What is beauty? What is goodness? Tanizaki presents a calculatingly messy train of thought that waxes poetic. It is essay-poetry, in a sense. At the same time, I could not fully embrace Éloge de l'ombre due to the lingering taste of an essentialism that felt almost deterministic. At a moment of rising insularity and nationalisms, I find the quest for "essences" troubling. There is a fine line that shapes the difference between understanding how aesthetics and ways of doing arise from culture, and prescribing a certain way of doing as essentially "Japanese". And while Tanizaki displays a degree of self-consciousness as to the development of cultural norms within specific contexts and circumstances, he also does not hesitate to issue very clear-cut assertions that read too much like givens or truths about what a group people is "essentially" like. Nonetheless, a book I look forward to revisiting.

Illuminations

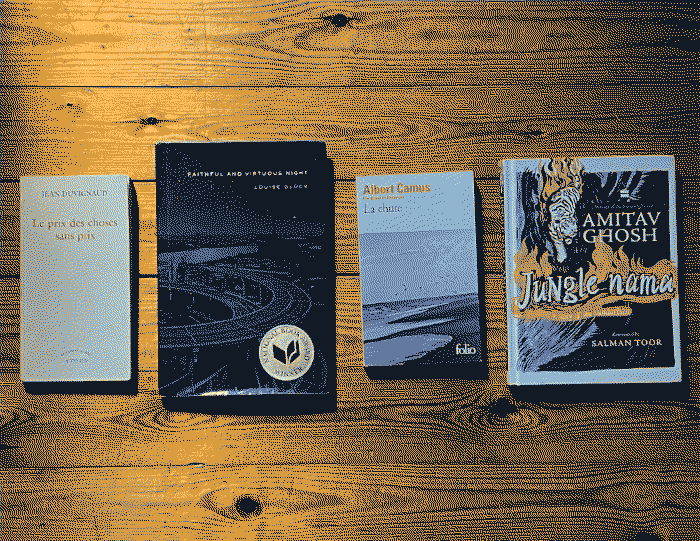

I have read two illustrated works during these first six months of 2025, Jungle Nama: A Story of the Sunderban by Amitav Ghosh and Salman Toor, and Looking for Luddites by John Hewitt. Both books made me reflect on the interplay between text and visual arts, which I think is very pertinent at a time that many predict (and/or lament) that both will be mechanized away.

This was my second reading of Jungle Nama, which I bought from Araku, a coffee shop we frequented during our stay in Bengalore. Looking for Luddites was found at a magazine and stationary shop I am fond of in Bristol: Rova. In a way, I encountered both books as artefacts that caught my passing eye.

For many decades, the predominant mode of thought has placed illustration as subservient to the written word. And in a way, illustration could even be considered as a "threat" to the seriousness of a book. Are picture books perhaps not "real books"? Jungle Nama and Looking for Luddites demonstrate that it is not so (as do so many other brilliantly illustrated books, such as the Alice books). Illustrations here prove to be not merely decorative, but rather are as essential to the storytelling as the text. The unique perspective or "eye" of the illustrator (even in the case of Hewitt, who is also the writer) cannot be subtracted away.

It is interesting to think about these books together, what does the retelling of a Bengali myth about the Sunderban mangrove forest have to do with the retelling of the Luddites' uprising against industrialization in Northern England? So much, it turns out, as both little books explore the nature of human greed as well as the complex relationships between human settlement and the natural world. In both works, authors and illustrators look to the past to raise timeless concerns that are among the most urgent today due the generalized use of AI and the destruction of our ecosystems. In both works, the "expendability" of human life mirrors the "expendability" of ecosystems, animals, and all other forms of life.

A parting thought related to pertinence, I read Jungle Nama at the same moment that both India and Pakistan were, once again, at the brink of war. Authored by an Indian writer and illuminated by a Pakistani illustrator, the book stands as a powerful contrast to war, illustrating what could be possible by coming together instead.

Reconsiderations

I have recently re-read two books of Latin American poetry, the Chilean poet Alejandro Zambra's Mudanza and María Mercedes Carranza's El oficio de vivir, the latter of which I wrote about for the original August Reads entry. I bought both books at the Bogotá Book Fair (FILBO) in 2024, and I picked them up again when I was feeling nostalgic about not being at FILBO this year.

First, I realized that I enjoyed both books more on the second read, which confirms by experience the well-known adage that good poetry must be re-read. In a sense, this reencounter with Zambra and Carranza is part of a multi-year reconciliation with poetry that first begun with Louise Glück. I had initially failed to connect with poetry, despite my love for reading, and I then struggled with it as a university student after the "Poetry 101" teaching assistant took great pleasure in announcing that the course was meant to "weed out" students from the English major. I survived the course, but ultimately chose not to major in English.

I had already appreciated Carranza's work on my first read, however, I couldn't quite count it among my favorites because I found the collection's bleakness to weigh too heavy. Carranza masterfully conveyed the hollow feelings of depression, and it was almost too much to bear. On a second read, however, my initial reticence has given way. The shock of encountering Carranza's profound listlessness and melancholy has subsided, and I felt like this time I could better perceive the beauty she crafted from the shadows. Despite of everything, glimmers of life shone through the despair and with the despair. It is a special book, compiled by Carranza's daughter with a lot of thought and care. I wish Carranza's poetry could be better known outside of Colombia. (And I wish I could translate it.)

My thoughts have strayed far, as usual, so I will continue my 2025 book reflection in a second entry.

Other Interesting 2025 Reads

- "The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House"

- "Permacomputing Aesthetics: Potential and Limits of Constraints in Computational Art, Design and Culture"

- Andrea

23.05.2025 // The Comma Directory Restructuring

Bath, England ⬔

I've meant to write (and I always mean to write) about our arrival to Bath—which has been truly revitalizing and has offered some harmonious continuity to our time in Devon and Selgars Mill.

However, I have been occupied in the pruning and clipping of previous Comma Directory entries that, over time, seem to have grown unwieldy, outgrowing the categories and sub-categories we have plotted them into. It has taken me some time, and it has got me thinking.

Curatorship is a topic that has long interested me, and it has become more and more pertinent in navigating the complexities we encounter—growing complexities—many would say, as the world grows more and more complex with AI, a changing climate, the threat of war. But I would say, instead, that complexity was already here all along. It could been found in the simplicity of a leaf that photosynthesizes or the star that twinkles in the night sky.

Hence, there is a "primal" need to curate, or categorize, or simplify. These actions are not strictly synonymous, but tightly bound to each other. I think, at least.

The issue with trying to place an infinitely complex experience of existence into neat categories has long been discussed within science, philosophy, technology, art. Our representations of the world are limited, and that is precisely why they are meaningful. By placing limits, which is to say prioritizing some facets of existence over others, we voice a point of view. This is why diversity of representations is so important—but it doesn't mean that limits themselves are "bad." Without limits, without the brain's ability to curate the complexity of each passing moment, decision-making, survival, meaningful and directed action would all perhaps be impossible. It is known, after all, that the "infinite" choice of streaming platforms, food delivery, and dating apps can often be debilitating and paralyzing. As can be the "infinite" flow of news and social media posts.

And these choice-laden systems do not even begin to approach the true complexity of how our planetary systems operate, not to say the universe.

All of this to say, I have been toying around with The Comma Directory's Concepts, Media, and Travel pages. I have been questioning whether having a "Design" category is too broad, and what the difference between design and other creative practices is. And, should sub-categories be included into multiple categories or restricted to a single one? It might not help that lately Marc has been reading the book, What Design Can’t Do: Essays on Design and Disillusion.

Ultimately, what are these categories for? Which in the end is the same as asking: what is The Comma Directory for? Developing a system for categorizing main ideas and themes is at the heart of our founding concept. It is a work in progress, and in a sense, it always will be. The categories will always overlap in some ways that are perhaps uncomfortable, and maybe there will also be some gaps that are hard to fill. Imprecisions.

I can imagine that many may consider that AI is particularly well-suited for this task, with its powered up pattern-recognition. Feed it the texts and have it spit out a systematization that, with the right prompting, could be "better" than anything that we can produce manually. Less time consuming, too. Why not? Maybe, while it is at it, it can also generate the entries and the images.

If making "sense" of the everyday complexities that bombard us is one of the most important functions of our brains, if our ability to make purposeful decisions has to do with our brain's ability to curate, to pick and choose, to categorize and, therefore, judge—then the work we do manually at The Comma Directory is profoundly rooted in what it means to think. In our vibes-bent era peopled with all sorts of energies and traumas, "feeling" feels much more fashionable than "thinking." And while I find modern, postmodern, and contemporary critiques of rationality to be very important, I echo Camus in saying that, while I acknowledge the many limitations of "reasoning", I do not deny "reasoning" in it of itself. And I do not want to automate away the very mental processes that constitute reasoning, and which I perceive to be very closely linked to my own agency and liberty. Not to say that intuition and feeling do not play an essential role, a role that is perhaps more closely tied to reasoning than traditional dualist conceptions of thought allow.

Ultimately, when I sit down to edit, reorganize, redefine, and recategorize, it is almost like I can feel changes starting to blossom from within, in real time, as I focus and tinker with our little website. I feel new questions begin to emerge, ideas begin to form, old ideas begin to transform. Maybe that is also why this entry is growing so much more longer than I anticipated.

There is a pleasure too that comes with all this thinking, of feeling yourself being transformed by interacting with a challenge and all the difficult questions it brings with, even when you do not fully succeed (which is often the case). The pleasure I derive from the curation and restructuring of The Comma Directory is also akin to the pleasure of moving to a new home, finding the nooks and crannies in which different little aspects of life can fit into. Here, the washing, there, the books. It is as much the art of adjusting the space to our lives as our lives to the space. Which is why it has been very fitting to work on The Comma Directory's categorization system at the same time as we have been settling into Bath and creating our short-term home here.

So, what's changed on here? New sub-categories have appeared, emerging from nearly a year's worth of writing and living, which is exactly what we hoped for from the start. I have also re-arranged some major categories within Concepts. For example, "Writing" has become "Creation", to cover a broader range of creative acts that we engage with. Thanks to Marc, each entry has its own page now, and can be accessed via the little square next to the location. Within media, there is some restructuring ongoing related to each "media" type. While we started with just "Books" and "Film", now we have "Articles & Essays", "Lectures", and "Websites". I am working on new ways of displaying a growing list of favorites, and hopefully implement a Reading Journal and a Film Journal. The new "Reviews" sections will include scattered thoughts on the different media types, rather than reviews in the strict sense of the word. I feel joyful about what The Comma Directory has grown into so far, and what it can grow to be with some continued care and attention.

- Andrea

29.04.2025 // Lucidity and the Sun

Bath, England ⬔

Lucidity. A concept Camus explored in a few of his essays, and that in many ways echoes a kind of personal philosophy that Andrea and I have been developing. To us, lucidity means to see the world for what it is, instead of ascribing grand narratives or superstition to it as a way to console ourselves for the perceived "meaninglessness" of existence.

In The Stranger, Camus writes about a man named Meursault and describes his complete indifference to the world. Meursault is meant to be unrelatable. Someone who seems almost inhumane, and so, who would not be able to relate or empathize with us either. Through his actions and attitudes, Meursault reveals what Camus calls "the absurd," which has to do with the perceived absence of meaning in life. However, Camus also introduces symbolism to reveal that as humans, we can rebel against the absurd.

In the very first scene of the book, when Meursault finds out his mom died, his apathetic response is difficult to stomach, as it is later on, when he encounters the titular stranger. In both scenes, Meursault focuses on a light that flickers or the sun that blinds him. His fixation on light during moments in which more "important" things occur, like the death of his mother, increases the distance between Meursault and the reader.

The light and the sun to me represents two things in this book. On some level, the distance we feel between ourselves and Meursault serves as a reminder of our innate urge to care, even when the world appears to be meaningless. An urge to care that Meursault does not seem to experience.

But the depiction of light also serves as another reminder, that when we feel the weight of the absurd the most, the shining light can set a path forward. The light shines on our skin and makes us see, and so it reminds us to be present. When we are present and experience the world for what it is, lucidly, we can revolt against the absurd.

This idea of lucidity and Camus' articulation of this concept was eloquently spelled out in a recent episode of Philosophize This on The Stranger, and I felt myself just nodding along in agreement.

- Marc

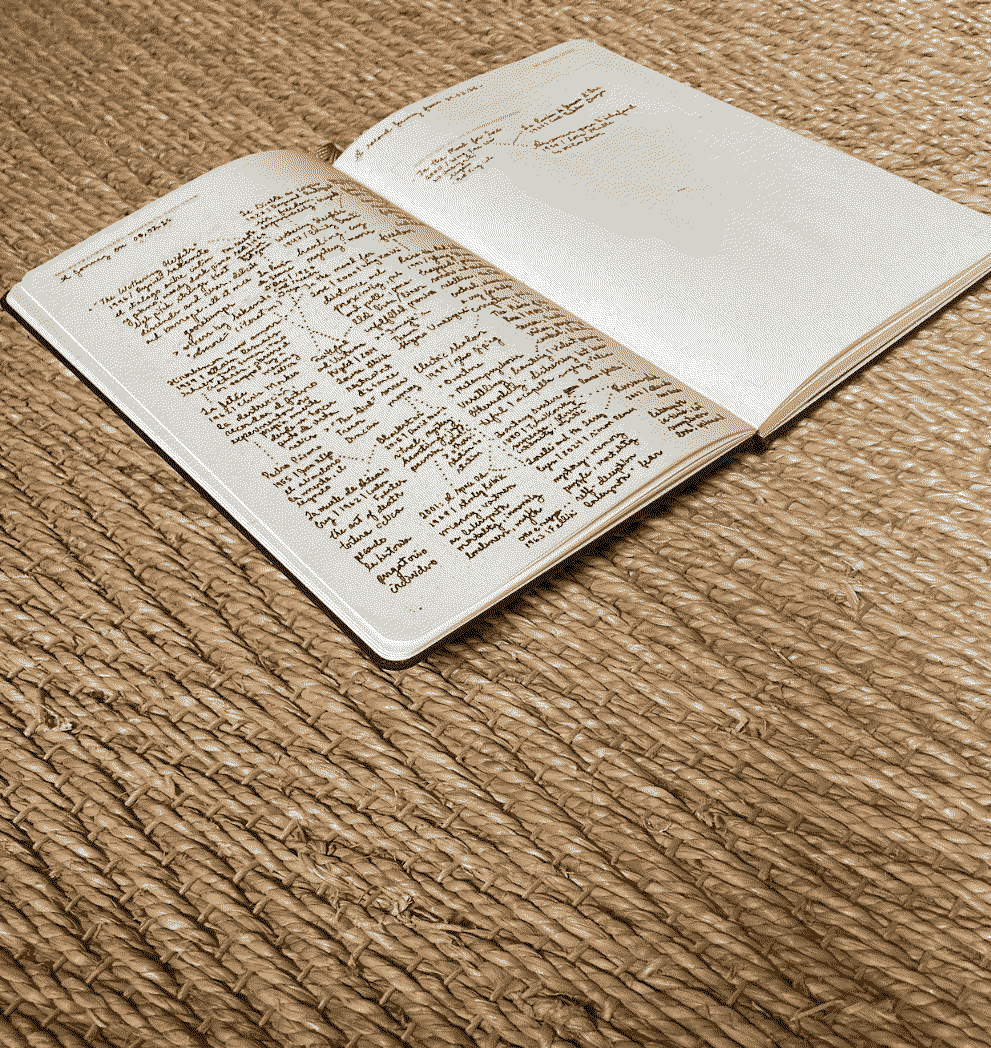

04.04.2025 // Pequeña bitácora bibliográfica I (08.2024 - 03.2025)

Uffculme, England ⬔

Around the time we first began to build Comma Directory, I acquired a little notebook which I wrote about in my very first post: "The Small Bibliographic Log" from the independent Colombian press, Rey Naranjo. Almost eight months later, the log is now filled to the brim with the readings and thoughts that have accompanied me from Colombia to Cyprus to Sweden to France, and finally, to England.

To commemorate the completion of my first pequeña bitácora bibliográfica, I have picked out a selection of quotes, some of them I have had to dig out of the tight corners that I stuffed them into as I ran out of space on the page. And so, ...

"Recuerdo que [...] escribía sobre toda la superficie del papel, sin respetar ningún margen. Eso me daba la sensación de llenar completamente un vacío".

– Mario Bellatin, El libro uruguayo de los muertos

"At the end of my patient reconstruction, I had before me a kind of lesser library, a symbol of the greater, vanished one: a library made up of fragments, quotations, unfinished sentences, amputated stumps of books."

– Umberto Eco, The Name of the Rose

« Nous voyons ces filets, leur beauté, leur appartenance tout à la fois à la liberté et à la capacité de capturer, oui capturer. »

– Franklin Arellano & Julia Bejarano López, Entretierras

"Suspended over the abyss, the life of Octavia's inhabitants is less uncertain than in other cities. They know the net will last only so long."

– Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities

"What is the consciousness of guilt but the arena floor rushing up to meet the falling trapeze artist? Without it, a bullet becomes a tourist flying without responsibility through the air."

– Richard Condon, The Manchurian Candidate

« Est-il aucun moment

Qui vous puisse assurer d'un second seulement ? »

– Jean de La Fontaine, Fables Choisies

« Il faut sinon se moquer, en tout cas se méfier de bâtisseurs d'avenir. Surtout quand pour bâtir l'avenir des hommes à naître, ils ont besoin de faire mourir les hommes vivants. L'homme n'est la matière première que de sa propre vie. »

– Jean Gino, Refus d'obéissance

"Whatever he did allowed him to be told [...] that he indeed existed, that he was not, as he had always dreaded, a figment of his own imagination, or of God's imagination, who disappeared when the lights went out."

– Richard Condon, The Manchurian Candidate

"¡Morir, Dios mío, morir así tísica a los veintitrés años, al comenzar a vivir, sin haber conocido el amor [...] morir sin haber realizado la obra soñada, que salvará el nombre del olvido; morir dejando al mundo sin haber satisfecho las millones de curiosidades, de deseos, de ambiciones [...]"

– José Asunción Silva, De sobremesa

"Pienso, antes de ponerme polvos

que aún no he comenzado

y ya estoy por terminar".

– María Mercedes Carranza, El oficio de vivir

« Elle rêvait aux palmiers droits et flexibles, et à la jeune fille qu'elle avait été. »

– Albert Camus, L'exile et le royaume

"I think here I will leave you. It has come to seem

there is no perfect ending.

Indeed, there are infinite endings.

Or perhaps, once on begins,

there are only endings."

– Louise Glück, Faithful and Virtuous Night

"I shall soon enter this broad desert, perfectly level and boundless, where the truly pious heart succumbs in bliss. I shall sink into the divine shadow, in a dumb silence and an ineffable union. And in this sinking, all equality and all inequality shall be lost [...] I shall fall into the silent and uninhabited divinity, where there is no work and no image."

– Umberto Eco, The Name of the Rose

"In the midst of the word he was trying to say;

In the midst of his laughter and glee,

He had softly and suddenly vanished away—

For the Snark was a Boojum, you see."

– Lewis Carroll, The Hunting of the Snark

- Andrea

17.03.2025 // Solange.

Uffculme, England ⬔

It has been a while since I last read and wrote. Work has been overwhelming, and the time I had to spare went into exploring the fundamentals of Linux.

But today, I finally managed to read a bit again. When I was younger I used to hate Swedish literature, perhaps because of traumatic recall to school. However, reading in a language other than English–especially in a Swedish from a time when the world carried less universal cultural references–is interesting. And thus, I have discovered a newfound love for Swedish literature.

I have begun to read Willy Kyrklund's Solange. It kicks off with a poem and an intro I want to share:

Where does all song go, that becomes suffocated and trapped?

Where does all hope go, that reaches nothing?

Could be that it abounds in the earth and water.

Could be that it whistles in the wind all around.

– Karin Boye

Or in Swedish:

Vart går all sång, som blir kvävd och innestängd?

Vart går all längtan, som når ingenting?

Kanhända den i mullen och vattnet ligger mängd.

Kanhända den viner i vinden omkring.

– Karin Boye

Followed by this intro:

This story shall tell the tale of Solange and Hugo. It carries, thus, not both names–Solange and Hugo. It carries only the name of the loved one: Solange.

- Marc

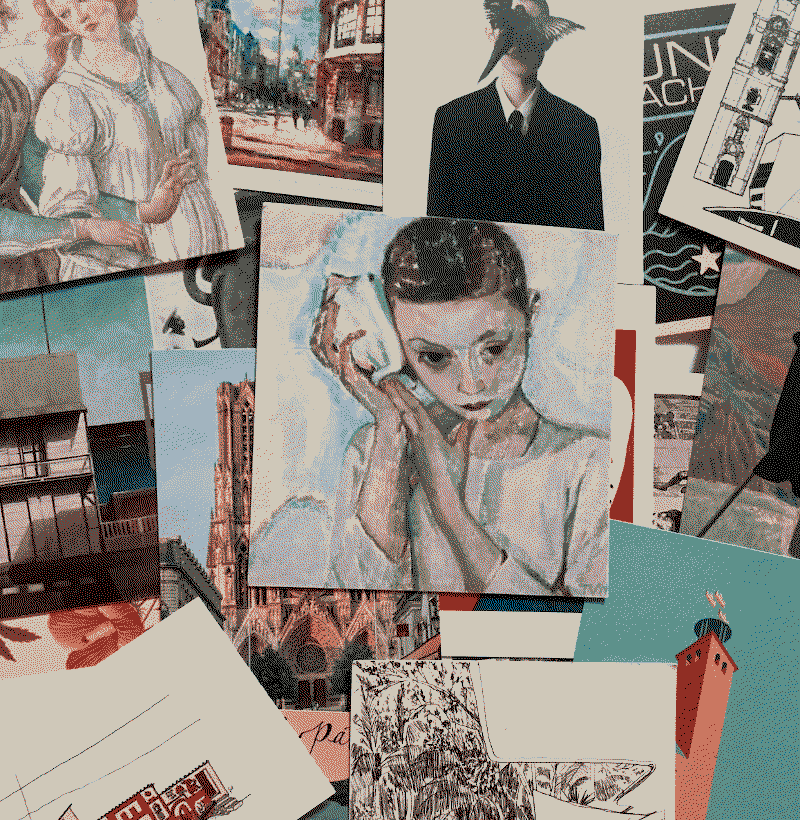

21.02.2025 // Constellations

Villecien, France ⬔

When the world appears to be pregnant with possibility, I take it as an invitation to embark upon a journey. Or, when I embark on a new journey, the world often appears to suddenly be pregnant with possibility, such as it appears to me now, after some recent day trips to Paris. But even after returning to the rolling muddy hills of the Yonne, I continue to be restless, yearning to visit and revisit as I have just done at the Palais-Royal, the courtyard of the Louvre, the narrow roads from Opera to Châtelet and the Centre Pompidou.

Wandering up and down the streets of a beloved city brings me a quiet but intense joy, akin to the feelings evoked by my favorite books, films, images, music. And so, I decided to embark on another journey, but this time through my memory, the internet, and some ink.

It has resulted in maps and constellations of those special works of art that move me and renew my gaze. Perhaps these are the transcendental feelings that others find in religion, ritual, patriotism, and/or mind-altering substances. I guess this could be a creative ritual of sorts, but I find the language around ritual and transcendence to have become so tired lately.

So, here is a brief inventory of my eclectic mental re-collections of sights, sounds, and feelings.

Books

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë

Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë

Le Diable au corps by Raymond Radiguet

The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco

La muerte de Artemio Cruz by Carlos Fuentes

Pedro Páramo by Juan Rulfo

Faithful and Virtuous Night by Louise Glück

Music

"The Wuthering Heights" by Sakamoto Ryuichi

"Amore" and "Solitude" by Sakamoto Ryuichi

"The Girl - Theme" by Trevor Duncan

"Yumeji's Theme" by Umebayashi Shigeru

"Romeo and Juliet" by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

"Overture" and "Metempsychosis" by Zhao Jiping

"Blackstar" and "Station to Station" by David Bowie

Film

Les Quatre Cents Coups by François Truffaut

Raise the Red Lantern by Zhang Yimou

Russian Ark by Aleksandr Sokurov

2001: A Space Odyssey by Stanley Kubrik

La jetée by Chris Marker

In The Mood for Love by Wong Kar Wai

L'Ascenseur pour l'échafaud by Louis Malle

Hiroshima mon amour by Alain Resnais

La Passion de Jeanne d'Arc by Carl Theodor Dreyer

The Seventh Seal by Ingmar Bergman

And More

Lorelei and the Laser Eyes by Simon Flesser & Simongo

- Andrea

29.10.2024 // Personal Tools

Paramytha, Cyprus ⬔

Recently, I finished up Donald Norman's An Invisible Computer. It's a fantastic book, probably one of my favorite books, and it starts off with a powerful quote:

"The personal computer is perhaps the most frustrating technology ever. The computer should be thought of as infrastructure. It should be quiet, invisible, unobtrusive, but it is too visible, too demanding. It controls our destiny. Its complexities and frustrations are largely due to the attempt to cram far too many functions into a single box that sits on the desktop. The business model of the computer industry is structured in such a way that it must produce new products every six to twelve months, products that are faster, more powerful, and with more features than the current ones."

As much as I like the book, however, there is one important concept that I disagree with. Norman titles and concludes the book with this idea: that technology should be completely invisible. By invisible, he means that technology should blend so seamlessly into our everyday life that we do not notice it is there.

"[.. talking about the goal of technology] The end result, hiding the computer, hiding the technology, so that it disappears from sight, disappears from consciousness, letting us concentrate upon our activities, upon learning, doing our jobs, and enjoying ourselves."

Sounds great in theory, in practice of course what we find is that companies make something that is easy to use, and then do not necessarily act in the users' best interest, but the user is stuck with what the company provided and is neither empowered to seek out other options nor fix it. I think this is an anti-pattern, and I talk about this in depth in my essay, The Curse of Convenience.

However, there is also another section that I found particularly interesting and shines a light on the direction where I think technology should go, which is Norman's idea about what makes a good tool. Norman has this to say:

"Good tools are always pleasurable ones, ones that the owners take pride in owning, in caring for, and in using. In the good old days of mechanical devices, a craftperson's tools had these properties. They were crafted with care, owned and used with pride. Often, the tools were passed down from generation to generation. Each new tool benefited from a tradition of experience with the previous ones so, through the years, there was steady improvement."

I do not feel like modern phones and computers are like this kind of tool. A good retro camera is something we learn inside out, with its quirks and unique abilities, and becomes part of our craft and personality. This is not so much the case with a modern iPhone. Modern technology removes as much personalization as possible and makes it hard to repair for the sake of convenience, looks and ease-of-use. That means that you do not put effort into truly knowing your tool nor personalizing it, and so as a result, do not appreciate it as much. Instead of customizing and learning about your unique device, you buy a new one, that acts just like the old one. Devices become impersonal and invisible.

In a recent interview, Norman laments the fact that his all time best-seller, Design of Everyday Things, did not cover that tools should be designed to be repairable too. To me, repairability is in opposition to his idea of technology becoming invisible. At the same time, I think repairability and customization go hand in hand with his idea that you should feel pride in owning a tool, and that that is what makes a good tool. A device that you tweak and make truly your own, you will care for more and want to repair as well. As I replace parts of my Thinkpad and change the way it looks and feels, I find it becomes more personal to me.

- Marc

30.09.2024 // War and Words

Lofou, Cyprus ⬔

Today we are in Lofou, a small village located 20 minutes north of Paramytha. It is another dreamy place that has preserved its beautiful stone architecture. In the café-restaurant that we sit at, a calm and cool atmosphere gives peace. We are surrounded by books, ceramics, dried plants, wood, art, the blue sky, and a green garden.

I have Javier Darío Restrepo’s Pensamientos: Discursos de ética y periodismo with me, which I read from a beautifully and simply designed armchair. Pensamientos reminds me of home. Life feels joyful.

And yet, whenever I pull up a map, I am reminded that we are now just off the coast of Lebanon. Perhaps an hour-long flight from Gaza. If I zoom out, I notice that we are on the same longitude as Ukraine, we share the same time zone.

I was born surrounded by violence. In Bogotá, you are always on your guard, even if the city is safer now than what it used to be, and a whole lot safer than what other parts of Colombia are still like today. Being here now, in this idyllic village, the contrast feels stark.

During a brief period in my early adulthood, (outright) war between nations went from feeling unthinkable to almost inevitable. I know this isn’t true, violence and injustice have been and continue to be ever-present. The turn of the century was incredibly bloody for Colombia with the "war on drugs." But it does feel that now there has been a broader mental shift: that before war and violence were somehow more unacceptable globally, and so different actors undertook violence in slyer and stealthier ways. Political discourse around military attacks and violent action was not so forthright. Some people may say, as has been said about Trump, “at least they’re being honest now, showing their true colors.”

However, I disagree. I think that the fact that a full-scale war was “unthinkable” for many people was a good thing. The fact that we have mental red lines is important, even if humanity does not always live up to these standards. To me, the goal should be to denounce and expose the ways governments, businesses, and individuals get around what is deemed just or right, and the ways in which hypocracy takes shape. We should hold leaders accountable for lofty speech promoting peace and tolerance, make them meet the standard, instead of giving in and making war and violence an “acceptable” and “inevitable” part of our everyday in the name of "honesty."

For a long time, I’ve felt a natural pull towards pacifism. However, I understood well the people who critiqued it, we need to defend ourselves from those who commit harm after all, don’t we? We need to be able to fight back, right? What’s the alternative?

While I don’t have any answers, I have realized I need to listen to that instinct that protests against violence, conflict, and war. It is an instinct that has been coupled with a life-long interest in literature and art that expresses and describes the ravages of systematized violence: from Primo Levi, Tim O’Brien and Harper Lee to Maryse Condé, Alain Resnais, and Isabel Allende. It was first the memoirs from Holocaust survivors followed by the accounts of the military dictatorships in South America and then the testimony of the brutality of slavery in the Caribbean that have over time constructed my conviction in justice, freedom, and accountability, but also at the same time, for nunca más.

“Never again” is always associated with World War II, but in Colombia, never again continues to be called for even as Colombians continue to suffer and die every day due to ongoing violence. Our “armed conflict” is unique in the way that the categories of victims and victimizer are not always so neatly separated. It is as the writer Rodolfo Celis Serrano describes in his autobiographic short text on life in the Usme neighborhood of Bogotá: there are things that he did while living under the threat of violence that still bring him shame and guilt. Celis was displaced from his home, a victim of the armed groups that took over the territory, and yet he himself complicates the category of “victim” by highlighting his own guilt. In Colombia, we have to reckon with reintegrating combatants and civilians of all types into peaceful communal living, while at the same time trying to balance this with the pursuit of justice and accountability.

And there are so many Colombian thinkers, artists, and activists that have been working through the inherent paradoxes of prolonged systemic violence for years.

One of them was Javier Darío Restrepo, who I am currently reading. For my next log entry, I want to reflect on Restrepo’s writing along with the work of Jean Giono, another author who I also read and rediscovered this month.

Their writing has given me much to think about what peace means, as real action and not just a “utopian” concept. In their writing, I’ve found that same visceral rejection to war and violence that I feel—that war is senseless at its core, even with all the justifications that we try to dress it up with. In their writing, I’ve also confirmed that this rejection of war does not entail sacrificing strong convictions about rights and wrongs, it doesn’t equal apathy or “neutrality” in the face of cruelty, injustice, and inhumanity.

“El carácter del conflicto, su prolongación en el tiempo, la complejidad y multitud de los elementos en juego, el constante juego de la desinformación—que no es accidental sino parte de la táctica guerrera—, crean una atmósfera de confusión tal que la gente muere todos los días sin saber por qué muere”. – Javier Darío Restrepo, Pensamientos (p. 221)

« Il faut sinon se moquer, en tout cas se méfier des bâtisseurs d’avenir. Surtout quand pour battre l’avenir des hommes à naître, ils ont besoin de faire mourir des hommes vivants. » – Jean Giono, Refus d’obéissance (p. 14)

- Andrea

22.09.2024 // Chautauqua

Paramytha, Cyprus ⬔

Currently, I am reading the book Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, and it is divided into several Chautauquas. Chautauquas began as part of a social movement during mid-20s America and they consisted of educational events full of "entertaining lectures, performances and/or concerts". The story of Zen And The Art Of Motorcycle Maintenance uses this concept to deliver philosophical insights in a way that is more entertaining to the reader, and uses, as you might guess, motorcycle maintenance to talk about what is the meaning of quality and why quality matters.

- Marc

11.09.2024 // August Reads

Bogotá, Colombia ⬔

While we are now well into September, I wanted to take a moment to reflect on some memorable August reads, books that I still think about and will be thinking about for a while.

I read two books last month, one poetry and one prose (very unconventional prose, however).

El oficio de vivir, or (roughly) The craft/work of living, is a collection of poetry by María Mercedes Carranza. Compiled posthumously and prefaced by her daughter, the collection sinks, poem by poem, deeper into the despair that plagued Carranza, especially in her final years. Despair about aging, despair about Colombia’s endless violence, despair about injustice, meaninglessness, despair about despair. Death weighs heavy on almost every page. Her words manage to covey the hollowness of depression in a way that I have not seen captured in any other piece of writing (even books and memoirs about war or genocide). It is grim, very grim.

El libro uruguayo de los muertos, or The Uruguayan Book of the Dead, on the other hand was much less grim, despite of the title. It did take me a very long time to read. Along with García Márquez’s El otoño del patriarca, it might be one of the toughest books I’ve ever gone through. In short snippets destined to a mysterious correspondent, Mario Bellatin melds fact and fiction to speak about everything and anything. Some themes do stand out: writing, publishing, illness, death, family, truth, falsehood and mysticism. Like the Twirling Dervishes he describes, cyclical snippets of narrative appear, disappear, only to reappear later, the same or almost the same or altered incomprehensibly. Temporality is warped, contradictions appear, and, as a reader, offering resistance only makes the read more painful. At some point you just have to let go and let Bellatin take you on a trip that goes round and round. And in the end, I was left a bit dizzy.

El oficio de vivir was close to making it on my favorites list—it is a true work of art. But the art that resonates with me the most is that which peers into the void, but with defiance. There is a will to live and an affirmation of life, the renewal of life. With Carranza, we succumb to the void, even if the last poem of the collection offers a glimmer of hope.

Mario Bellatin’s Salon de belleza (Beauty Salon) is one of my favorite books, but I can’t say the same for El libro uruguayo de los muertos. There are very interesting ideas about the nature of truth and fiction, about the pain of creation, and about life, death and creation as cyclical. The unconventional form resonated with these themes, but maybe it went on for too long. But then again, watching Twirling Dervishes perform is fascinating, but it can also feel eternally long after a while. But isn’t that what we’re all after, eternity? Reading El libro uruguayo de los Muertos definitely felt like it took an eternity too, but maybe that's what Bellatin was trying to do—approach eternity, which also means to approach death.

Other Interesting August Reads

- “Programming is Forgetting: Toward a New Hacker Ethic”

- “The Betrayal of American Border Policy”

- “The Funeral: At a Loss” (recommend reading this only after watching Itami Juzo's film)

- Andrea

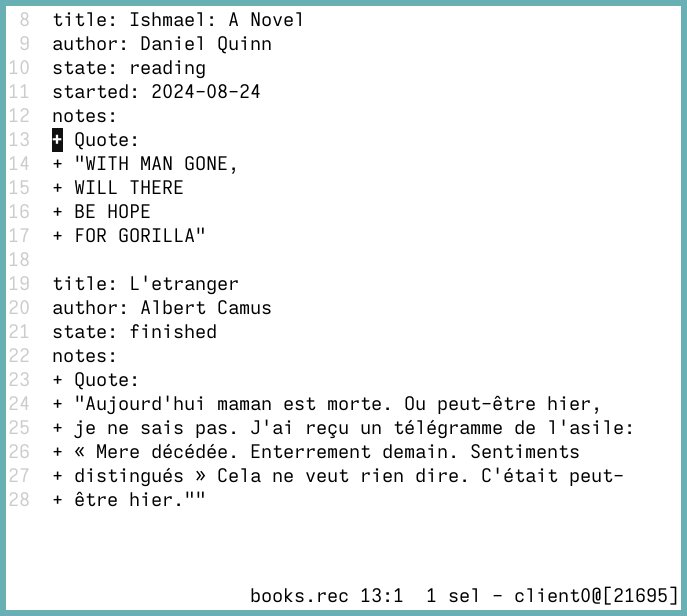

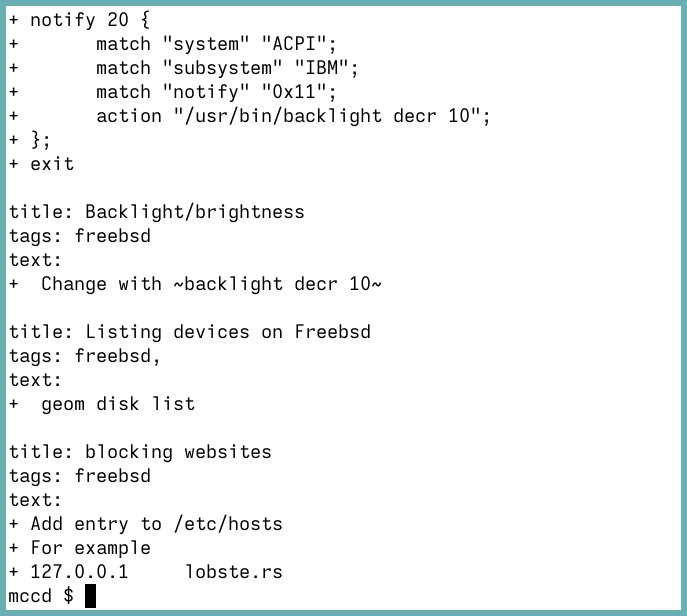

25.08.2024 // Personal Database with Recutils

Bogotá, Colombia ⬔

I have begun using recutils to build a database of what I have read, watched and also for storing references on how to do things.

The tool has a decent amount of utilities for querying data and its simple formatting means that even if recutils one day stops working, it would be trivial for me to build my own replacement.

The usage becomes simple. To find all FreeBSD specific information, I can simply run the recsel -q freebsd ~/refs.rec and I will find all my Freebsd related references. I made an alias of it so I just have to type refs freebsd.

refs freebsd.- Marc